Tag: trademark

A. Introduction

The dipartite structure of the American patent system, comprising the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and the federal Article III court system, leads to interesting interactions between rulings made in each of the distinct subsystems. This is especially relevant to the patent system in the context of claim construction. Moreover, because the Federal Circuit has sole jurisdiction over patent cases, their unique frameworks for analyzing procedural and substantive legal issues lead to facially surprising outcomes. Two recent cases applying Federal Circuit precedent illustrate this in relation to the judicial application of collateral estoppel, or issue preclusion.

B. The Broad Strokes of Issue Preclusion

Issue preclusion stands for the idea that, “[o]nce a matter [has been] properly litigated, that should be the end of the matter for the parties to that action.” It is similar, in that sense, to res judicata, but issue preclusion has a distinct scope. Issue preclusion applies where the issue had been previously, properly litigated and the decision on the matter was material to the case in which it was decided. The more important distinction, however, between issue preclusion and res judicata is that issue preclusion does not require “mutuality” between the parties in the case where issue preclusion is being asserted. In other words, the second litigation does not need to be between the same two parties, as is the case with res judicata.

The Federal Circuit, the relevant circuit for this discussion, recognizes exceptions to issue preclusion. The exception with the most interaction with rulings from the PTAB (the appeals board of the USPTO) is that issue preclusion does not apply where the subsequent proceeding applies “a different legal standard.” This was the deciding exception in the two cases that help us understand the implications of this Federal Circuit exception to issue preclusion.

C. Standard Disparities Between PTAB and Article III Courts

The USPTO applies its own particular standards during PTAB proceedings. These are statutorily defined, further interpreted in federal regulations, and expounded upon from the Manual for Patent Examination and Procedure. For the purpose of understanding how PTAB rulings interact with decisions of Article III courts, we will focus primarily on rules relevant to claim construction and patent validity.

- Claim Construction in Front of the PTAB and the Courts

In evaluating the validity of patent claims, the USPTO applies a “broadest reasonable interpretation” when constructing, or determining the meaning of, the claims of the patent under examination. This is relevant during initial examination of the patent by the USPTO’s examiners and on appeal of a final rejection to the PTAB. In other words, the USPTO and PTAB look for the broadest interpretation of the language of the claims that remains reasonable. The courts, on the other hand, apply the Phillips Standard, which “constructs” the claim as one of ordinary skill in the field would understand it in light of the specification and prosecution history any record produced during the original examination of the patent.

This was a potential factor in the rejection of the application of collateral estoppel in our first case, DDR Holdings, LLC v. Priceline.com LLC. Interestingly, it was not a deciding factor in the disposition of the question of issue preclusion. As issue preclusion is an affirmative defense, it must be raised in the answer a complaint. DDR Holdings, however, failed to raise issue preclusion until their brief. The court explicitly notes that this is fatal, in and of itself, but nevertheless evaluates the merits of the request for collateral estoppel. In this case, DDR Holdings sought to estop Priceline from arguing that “merchants providing a service” were not merchants covered under DDR Holdings’ ‘399 patent’s definition of a merchant. Priceline was arguing this based on the prosecution history of the ‘399 patent. During prosecution and initial examination, DDR Holdings had deleted any reference of “providing services” from the definition of merchant within the specification. DDR Holdings had, however, incorporated this earlier, service-inclusive definition, by incorporating the containing preliminary application by reference.

In light of this, the PTAB, during Inter Partes Review initiated by Priceline over the asserted ‘399 patent, found that the portion of the specification nominally defining “merchant” was not, in fact, definitional. Instead, the PTAB applied the broadest reasonable interpretation standard during the Inter Partes Review and found “merchants” to include “producers, distributors, or resellers of the goods or services to be sold.” In other words, the specification did not limit “merchants” because the PTAB did not find sufficient evidence to show that DDR Holdings intended to define “merchant” restrictively via the specification. As such, the broadest reasonable interpretation of “merchant” within the claims would necessarily include purveyors of services.

With this particular ruling, DDR Holdings asserted that the matter had been properly litigated and, therefore, Priceline should be collaterally estopped from asserting their differing construction of merchants in the case before the court. The court noted, however, that it was not bound by the decision of the PTAB because that decision applied the “Broadest Reasonable Interpretation” instead of the court’s Phillips Standard. Because the Federal Circuit, and by extension the district court, must apply the Phillips Standard, issue preclusion could not apply. In other words, Priceline could assert its construction that would exclude “service” providing from the ‘399 patent’s definition of merchants.

Under this standard, the Federal Circuit found the discussion in the ‘399 patent’s specification of “merchant” to be definitional. Furthermore, the Federal Circuit found that the deletion of “services” between the provisional and non-provisional patent to be material and, under the Phillips Standard, found it to explicitly exclude services from the ‘399 claim coverage.

- Inter Partes Review and Collateral Estoppel

The second case, Kroy IP Holdings, LLC v. Groupon, Inc., is more narrowly focused on challenges to invalidity, in the form of Inter Partes Review, before the PTAB. During an IPR proceeding, the PTAB applies a preponderance of evidence standard when determining if a patent is valid or invalid. This is at odds with the standard applied in Article III courts, which instead apply the clear and convincing evidence standard.

In Kroy, Groupon had previously initiated IPR of patents asserted by Kroy IP Holdings. In the IPRs, Groupon prevailed and the asserted patents were found to be invalid. The district court then held that Kroy IP Holdings was collaterally estopped from re-litigating the patent validity presented. After Groupon’s motion to dismiss was granted, Kroy IP Holdings sought appeal, arguing that, given the differing standards, collateral estoppel should not have applied, among other things.

The Federal Circuit ultimately decided in Kroy IP Holding’s favor. First, they noted that, on its face, collateral estoppel—or issue preclusion—could not apply here. This finding was the result of the lowered standard of proof required in front of the PTAB versus that required in front of the court.

The court then addressed a further exception to this exception. Groupon had argued, in favor of precluding Kroy IP Holding form re-litigating patent validity, that the Federal Circuit’s previous decisions stated that PTAB invalidity findings were themselves preclusive. The Federal Circuit disagreed and clarified. The Court explained that PTAB findings on validity only became preclusive once the Federal Circuit had affirmed them. A natural result of this, as described by the court, is that claims found invalid by the PTAB remain in existence until the decision is appealed to the Federal Circuit and affirmed or a district court, applying their heightened standard, independently finds the claims invalid. In other words, only once patent validity has been evaluated under the clear and convincing standard, either on appeal to the Federal Circuit or as a matter of first impression in front of a district court, does the disposition gain preclusive effect.

Because the District Court based its dismissal on the preclusive effect of the PTAB findings and said PTAB findings had not been appealed to the Federal Circuit, the court reversed and remanded.

D. Conclusion

The cases discussed above illustrate a distinct challenge that faces the dipartite American patent system. Because of the differing standards applied by the two bodies that hold sway over patent litigation, parties can be given a functional second bite at the apple when moving between the USPTO and Article III courts. This system is ultimately imperfect and creates duplicative litigation, as demonstrated in both of these cases. This is counterbalanced by the increased efficiency the USPTO and PTAB ostensibly provide to the American intellectual property system. In summary, because of the structure of the American patent system, issue preclusion—or collateral estoppel—remains difficult to invoke in patent litigation.

INTRODUCTION

“Zombies” may be pure fiction in Hollywood movies, but they are a very real concern in an area where most individuals would least expect – trademark law. A long-established doctrine in U.S. trademark law deems a mark to be considered abandoned when its use has been discontinued and where the trademark owner has no intent to resume use. Given how straightforward this doctrine seems, it is curious why the doctrine of residual goodwill has been given such great importance in trademark law.

Residual goodwill is defined as customer recognition that persists even after the last sale of a product or service have concluded and the owner has no intent to resume use. Courts have not come to a clear consensus on how much weight to assign to residual goodwill when conducting a trademark abandonment analysis. Not only is the doctrine of residual goodwill not rooted in federal trademark statutes, but it also has the potential to stifle creativity among entrepreneurs as the secondhand marketplace model continues to grow rapidly in the retail industry.

This dynamic has led to a phenomenon where (1) courts have placed too much weight on the doctrine of residual goodwill in assessing trademark abandonment, leading to (2) over-reliance on residual goodwill, which can be especially problematic given the growth of the secondhand retail market, and finally, (3) over-reliance on residual goodwill in the secondhand retail market will disproportionately benefit large corporations over smaller entrepreneurs.

A. The Over-Extension of Residual Goodwill in Trademark Law

A long-held principle in intellectual property law is that “[t]rademarks contribute to an efficient market by helping consumers find products they like from sources they trust.” However, the law has many forfeiture mechanisms that can put an end to a product’s trademark protection when justice calls for it. One of these mechanisms is the abandonment doctrine. Under this doctrine, a trademark owner can lose protection if the owner ceases use of the mark and cannot show a clear intent to resume use. Accordingly, the abandonment doctrine encourages brands to keep marks and products in use so that they cannot merely warehouse marks to siphon off market competition.

The theory behind residual goodwill is that trademark owners may deserve continued protection even after a prima facie finding of abandonment because consumers may associate a discontinued trademark with the producer of a discontinued product. This doctrine is primarily a product of case law rather than deriving from trademark statutes. Most courts will not rely on principles of residual goodwill alone in evaluating whether a mark owner has abandoned its mark. Instead, courts will often consider residual goodwill along with evidence of how long the mark had been discontinued and whether the mark owner intended to reintroduce the mark in the future.

Some courts, like the Fifth Circuit, have gone as far as completely rejecting the doctrine of residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analysis and will focus solely on the intent of the mark owner in reintroducing the mark. These courts reject the notion that a trademark owner’s “intent not to abandon” is the same as an “intent to resume use” when the owner is accused of trademark warehousing. Indeed, in Exxon Corp. v. Humble Exploration Co., the Fifth Circuit held that “[s]topping at an ‘intent not to abandon’ tolerates an owner’s protecting a mark with neither commercial use nor plans to resume commercial use” and that “such a license is not permitted by the Lanham Act.”

The topic of residual goodwill has gained increased importance over the last several years as the secondhand retail market has grown. The presence of online resale and restoration businesses in the fashion sector has made it much easier for consumers to buy products that have been in commerce for several decades and might contain trademarks still possessing strong residual goodwill. Accordingly, it will be even more crucial for courts and policymakers to take a hard look at whether too much importance is currently placed on residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analysis.

B. Residual Goodwill’s Increasing Importance Given the Growth of the Secondhand Resale Fashion Market

Trademark residual goodwill will become even more important for retail entrepreneurs to consider, given the rapid growth in the secondhand retail market. Brands are using these secondhand marketplaces to extend the lifecycles of some of their top products, which will subsequently extend the lifecycle of their intellectual property through increased residual goodwill.

Sales in the secondhand retail market reached $36 billion in 2021 and are projected to nearly double in the next five years to $77 billion. Major brands and retailers are now making more concerted efforts to move into the resale space to avoid having their market share stolen by resellers. As more large retailers and brands extend the lifecycle of their products through resale marketplaces, these companies will also likely extend the lifespan of their intellectual property based on the principles of residual goodwill. In other words, it is now more likely for residual goodwill to accrue with products that are discontinued by major brands and retailers now since those discontinued products are made available through secondhand marketplaces.

The impact of the secondhand retail market on residual goodwill analysis may seem like it is still in its early stages of development. However, the recent Testarossa case, Ferrari SpA v. DU , out of the Court of Justice of the European Union is a preview of what may unfold in the U.S. In Testarossa, a German toy manufacturer challenged the validity of Ferrari’s trademark for its Testarossa car model on the grounds that Ferrari had not used the mark since it stopped producing Testarossas in 1996. While Ferrari had ceased producing new Testarossa models in 1996, it had still sold $20,000 in Testarossa parts between 2011 and 2017. As a result, the CJEU ultimately ruled in Ferrari’s favor and held that production of these parts constituted “use of that mark in accordance with its essential function” of identifying the Testarossa parts and where they came from.

Although Ferrari did use the Testarossa mark in commerce by selling car parts associated with the mark, the court’s dicta in the opinion referred to the topic of residual goodwill and its potentially broader applications. In its reasoning, the CJEU explained that if the trademark holder “actually uses the mark, in accordance with its essential function . . . when reselling second-hand goods, such use is capable of constituting ‘genuine use.’”

The Testarossa case dealt primarily with sales of cars and automobile parts, but the implications of its ruling extend to secondhand retail, in general. If the resale of goods is enough to qualify as “genuine use” under trademark law, then this provides trademark holders with a much lower threshold to prove that they have not abandoned marks. This lower threshold for “genuine use” in secondhand retail marketplaces, taken together with how courts have given potentially too much weight to residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analyses, could lead to adverse consequences for entrepreneurs in the retail sector.

C. The Largest Brands and Retailers Will Disproportionately Benefit from Relaxed Trademark Requirements

The increasingly low thresholds for satisfying trademark “genuine use” and for avoiding trademark abandonment will disproportionately benefit the largest fashion brands and retailers at the expense of smaller entrepreneurs in secondhand retail. Retail behemoths, such as Nike and Gucci, will disproportionately benefit from residual goodwill and increasingly relaxed requirements for trademark protection since these companies control more of their industry value systems. This concept will be explained in more detail in the next section.

Every retail company is a collection of activities that are performed to design, produce, market, deliver, and support the sale of its product. All these activities can be represented using a value chain. Meanwhile, a value system includes both a firm’s value chain and the value chains of all its suppliers, channels, and buyers. Any company’s competitive advantages can be best understood by looking at both its value chain and how it fits into its overall value system.

In fashion, top brands and retailers, such as Nike and Zara, sustain strong competitive advantages in the marketplace in part because of their control over multiple aspects of their value systems. For example, by offering private labels, retailers exert control over the supplier portion of their value systems. Furthermore, by owning stores and offering direct-to-consumer shipping, brands exert control over the channel portion of their value systems. These competitive advantages are only heightened when a company maintains tight protection over their intellectual property.

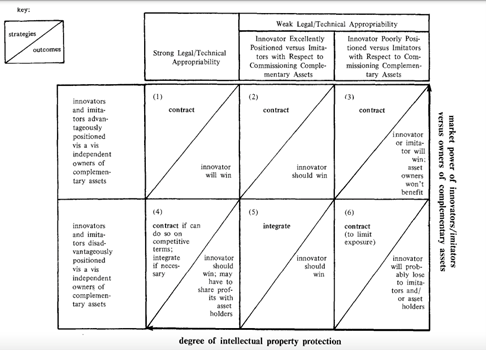

As portrayed in the figure below , companies maintain the strongest competitive advantages in cell one when they are advantageously positioned relative to owners of complementary assets, and they maintain strong intellectual property protection. In such situations, an innovator will win since it can derive value at multiple sections of its value system using its intellectual property.

CONCLUSION

Although there is little case law on the relevance of residual goodwill and secondhand retail marketplaces, it is only a matter of time until the largest fashion brands and retailers capitalize on increasingly low thresholds for demonstrating trademark “genuine use.” Courts and policymakers should now stay alert of these potential issues when dealing with trademark abandonment matters.

Rohun Reddy is a third-year JD-MBA student at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.