Tag: intellectual property

INTRODUCTION

We live in an insatiable society. Across the globe, particularly in the United States, everyone with an Instagram account knows that the “phone eats first.” Young professionals rush to happy hour to post the obligatory cocktail cheers video before they take their first sip. On Friday nights, couples sprint to their favorite spot or the up-and-coming Mediterranean restaurant to quickly snap a picture of the “trio of spreads.” Everyone from kids to grandparents alike are flocking to the nearest Crumbl every Monday to share a picture of the pink box and the half-pound cookie inside. Social media has created a food frenzy. We are more obsessed with posting the picture of a meal than eating the meal itself. While a psychologist might have a negative view of the connection between social media and food, the baker or chef behind the photogenic creation is ecstatic by the way platforms such as Instagram and YouTube bring new patrons into their storefronts.

Due to the rise of social media over the past twenty years, food has become an obsession in our society. Many of us are self-proclaimed “foodies.” Historically, food has not fit neatly into the intellectual property legal scheme in the United States. Trademark, trade dress, and trade secrets are often associated with food, but we rarely see recipes or creative platings receive patent or copyright protection. Intellectual property law is not as enthralled with food as many of us are, but pairing the law with social media may create another way to protect food.

A RECIPE FOR IP PROTECTION

There are four main types of intellectual property: patents, copyrights, trade secrets, and trademarks. The utilitarian and economic perspectives are the two main theories behind intellectual property law. The utilitarian purpose of food is to be consumed. Economically, the food business in America is a trillion-billion-dollar industry. Intellectual property law aims to promote innovation, creativity, and economic growth. All three of these goals can be found within the food industry; however, the recipe for intellectual property protection has yet to be perfected.

Patent law is designed to incentivize and promote useful creations and scientific discoveries. Patent law gives an inventor the right to exclude others from using the invention during the patent’s term of protection. To qualify for a patent, an invention must be useful, novel, nonobvious, properly disclosed, and made up of patentable subject matter. Patentable subject matter includes processes, machines, manufactures, compositions of matter, and improvements thereof. Novelty essentially requires that the patent be new. It is a technical and precise requirement that often creates the biggest issue for inventors. Novelty in the context of food “means that the recipe or food product must be new in the sense that it represents a previously unknown combination of ingredients or variation on a known recipe.” According to the U.S. Court of Customs and Patent Appeals, to claim protection in food products, “an applicant must establish a coaction or cooperative relationship between the selected ingredients which produces a new, unexpected, and useful function.”A person cannot simply add or eliminate common ingredients, treating them in ways that would differ from the former practice. There are very few patents for food, but common examples include Cold Stone Creamery’s signature Strawberry Passion ice cream cake and Breyer’s Viennetta ice cream cake.

Copyright law affords protection to creative works of authorship that are original and fixed in a tangible medium. Fixation is met “when its embodiment … is sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration.” The Supreme Court has stated, “that originality requires independent creation plus a modicum of creativity.” Copyrights are not extended to “any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery.” Food, specifically food designs, are typically not eligible “for copyright protection because they do not satisfy the Copyright Act’s requirement that the work be fixed in a tangible medium.” A chef does not acquire rights for being the first to develop a new style of food because this creation is seen as merely ideas, facts, or formulas. Furthermore, shortly after a food’s creation, it is normally eaten, losing its tangible form. Recipes alone are rarely given copyright protection because recipes are considered statements of facts, but “recipes containing other original expression, such as commentary or artistic elements, could qualify for protection.”

Trade secrets are more favorable to the food industry. Traditionally, trade secret law has encompassed recipes. To be a trade secret the information must be sufficiently secret so that the owner derives actual or potential economic value because it is not generally known or readily ascertainable. The owner must make reasonable efforts to maintain the secrecy of the information. It is unlikely that food design, the shape and appearance of food, will be given trade secret protection as “food design presents a formidable challenge to trade secret protection: once the food is displayed and distributed to consumers, its design is no longer secret.” However, certain recipes, formulas, and manufacturing and preparation processes may be protected by trade secret law. Regarding food and intellectual property, trade secrets are probably the most well-known form of IP. Examples of still valid trade secret recipes and formulas include Coca-Cola’s soda formula, the original recipe for Kentucky Fried Chicken, the recipe for Twinkies, and the recipe for Krispy Kreme donuts.

Trademark is the most favorable type of IP protection given to the food industry. Trademarks identify and distinguish the source of goods or services. Trademarks typically take the form of a word, phrase, symbol, or design. Trade dress is a type of trademark that refers to the product’s appearance, design, or packaging. Trade dress analyzes “the total image of a product and may include features such as size, shape, color or color combinations, texture, graphics, or even particular sales techniques.”

Different types of trademarks and trade dress receive different levels of protection. For trademarks, it depends on the kind of mark. Courts determine whether the mark is an inherently distinctive mark, a descriptive mark, or a generic mark. Similarly, trade dress receives different levels of protection depending on whether the trade dress consists of product packaging or product design. In the context of food, ‘the non-functionality of a particular design or packaging is required” for a product to receive protection as trade dress. Some examples of commonly-known trademarks include Cheerios, the stylized emblematic “M” logo from McDonald’s, and the tagline “Life tastes better with KFC.” Food designs that have federally registered trademarks under trade dress include: Pepperidge Farm’s Milano Cookies, Carvel’s Fudgie the Whale Ice Cream Cake, Hershey’s Kisses, General Mills’ Bugles, Tootsie Rolls and Tootsie Pops, and Magnolia Bakery’s cupcakes bearing its signature swirl icing.

SOCIAL MEDIA – THE LAST DEFENSE

When it comes to food, there is no recipe to follow to receive intellectual property protection, but social media can be a way for bakers, chefs, and restauranteurs to be rewarded for their creations and ensure creativity in the food industry. Social media influences the way businesses conduct and plan their marketing strategies. Many businesses use social media to communicate with their audience and expand their consumer base. Social media allows a chef to post the week’s “Specials Menu” to their restaurant’s Instagram, and in a few seconds, anyone who follows that account can post that menu on their account and share it with hundreds if not thousands of people. As noted previously, this single menu would not receive IP protection because it is primarily fact-based, not a secret, is obvious, and is likely not a signifier of the restaurant to the general public. However, the power of social media will bring hundreds of excited and hungry foodies to the business.

Social media alone cannot ensure that another chef or baker won’t reverse engineer the dish featured on the special’s menu, but social media has done what IP cannot. The various social media platforms embody what the framers of the Constitution were trying to accomplish through intellectual property when they drafted Article I centuries ago — the promotion of innovation, creativity, and economic growth. The Constitution states that “Congress shall have power to … promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries….” While there is no indication that the framers ever intended food to be a part of what they knew to be intellectual property, two hundred and fifty years later, it is clear that food is a mainstay in the IP world, even if it does not fit systematically into patents, copyrights, trademarks, or trade secrets. Unfortunately, the law has fallen short when addressing IP protection for the food industry; but, luckily social media has continued to fulfill the goal of intellectual property that the framers desired when it comes to the food industry.

Social media allows others to connect with the satisfying creation and gives chefs the opportunity to be compensated for their work. After seeing the correlation between the Instagram post and the influx of guests, the chef will be incentivized to create more. The chef will cook up another innovative menu for next week, hoping that she will receive the same positive reward again. The food industry is often left out, unable to fit into the scope of IP law, but through social media, chefs and bakers can promote innovation, creativity, and economic growth at the touch of their fingers.

Alessandra Fable is a second-year law student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

Introduction

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization granted state legislatures the authority to regulate abortion. The Court’s decision quickly led states, such as Texas and Arkansas, to enact trigger bans for the procedure. Prior to the Court’s ruling, data brokers had already begun selling location data for individuals visiting abortion facilities through ordinary apps. This data often provided details to where the individual traveled from and how long they stayed at the facility.

In the wake of Dobbs, concerns have come to light regarding the potential misuse of sensitive personal health data originating from period tracking apps. Questions have arisen concerning whether “femtech” app data can be used to identify and prosecute individuals violating abortion laws. Due to lax federal laws and regulations in the United States, the onus falls on femtech companies to immediately and proactively find ways to protect users’ sensitive health data.

What is “Femtech’?

The term “femtech” was coined in 2016 by Ida Tin, the CEO and co-founder of period tracking app Clue. Femtech refers to health technology directed at supporting reproductive and menstrual healthcare. The femtech industry is currently estimated to have a market size between $500 million and $1 billion. Femtech apps are widely used with popular period-tracking app Flo Health touting more than 200 million downloads and 48 million monthly users.

Apps like Clue, Flo Health, and Stardust allow individuals to record and track their menstrual cycle to receive personalized predictions on their next period or their ovulation cycle. Although femtech apps collect highly sensitive health data, they are largely unregulated in the United States and there is a growing push for a comprehensive framework to protect sensitive health data that the apps collect from being sold or provided to third parties and law enforcement.

Current Regulatory Framework

Three federal agencies have regulatory authority over femtech apps – the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”), United States Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”), and the Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”). Their authority over femtech data privacy is limited in scope. Furthermore, while the FDA can clear the apps for contraceptive use, greater focus has been put on the FTC and HHS in regulating femtech. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), administered by the HHS, fails to protect sensitive health data from being collected and sold, and femtech apps are not covered under the Act. The FTC is currently exploring rules on harmful commercial surveillance and lax data security practices following President Joe Biden’s July 2022 executive order that encourages the FTC to “consider actions . . . to protect consumers’ privacy when seeking information about and provision of reproductive health care services.” The executive order’s definition of “reproductive healthcare services” does not, however, seem to include femtech apps. Thus, a massive gap remains in protecting sensitive health data consumers willingly provide to femtech app who may sell or provide such data to law enforcement or third parties. Femtech apps generally have free and paid versions for users, which makes the issue all the more immediate.

The unease based on potential misuse of health data collected by “femtech” apps heightened following the FTC’s complaint against Flo. The agency alleged the app violated Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act (“FTCA”) by misleading consumers on how it handled sensitive health data. While the app promised to keep sensitive health data private, the FTC found the app was instead sharing this data with marketing and analytics firms, including Facebook and Google. Flo ultimately settled with the FTC, but the app refused to admit any wrongdoing.

FTC Commissioners Rohit Chopra and Rebecca Kelly Slaughter issued a joint statement following the settlement stating that, in addition to misleading consumers, they believed the app also violated the FTC’s Health Breach Notification Rule (“Rule”), which requires “vendors of unsecured health information . . . to notify users and the FTC if there has been an unauthorized disclosure.” The FTC refused to apply the Rule against Flo as such enforcement would have been “novel.” Such disclosures will help users navigate the post-Dobbs digital landscape, especially in light of news reports that law enforcement in certain states has begun to issue search warrants and subpoenas in abortion cases.

There is additional concern regarding femtech app’s potential location tracking falling into the hands of data brokers. The FTC recently charged Kochava, a data brokerage firm, with unfair trade practice under Section 5 of the FTCA for selling consumers’ precise geolocation data at abortion clinics. While Kochava’s data is not linked to femtech, in light of the FTC’s settlement with Flo, concerns of sensitive reproductive health data from femtech apps being sold is not out of the realm of possibility. Despite the FTC announcement on exploring new rules for commercial surveillance and lax data security, experts have expressed concern on whether such rulemaking is best done through the FTC or Congress. This is because the FTC’s rules are “typically more changeable than a law passed by Congress.”

As noted, most femtech apps are not covered under HIPAA nor are they required to comply. HIPAA encompasses three main rules under Title II: the Security Rule, the Privacy Rule, and the Breach Notification Rule. HIPAA is not a privacy bill, but it has grown to “provide expansive privacy protections for [protected health information] (“PHI”).” Due to the narrow definition of covered entity, there is little protection that can be provided to femtech app users under the current structure of HIPAA even though these apps collect health data that is “individually identifiable.”

Momentum for HIPAA to be amended so femtech may fall within the scope of covered entities may still fall short since HIPAA’s Privacy Rule permits covered entities to disclose protected health information (“PHI”) for law enforcement purposes through a subpoena or court-ordered warrant. While it does not require covered entities to disclose PHI, this permission could be troublesome in states hostile to abortion. Even if HIPAA’s definition of covered entities is expanded, it would still be up to the company to decide whether to disclose PHI to law enforcement. Some femtech companies, though, may be more willing to protect user data and have already begun to do so.

Future Outlook and What Apps Are Doing Post-Dobbs

In September 2022, Flo announced in an email to users that it was moving its data controller from the United States to the United Kingdom. The company wrote that this change meant their “data is handled subject to the UK Data Protection Act and the [General Data Protection Regulation].” Their privacy policy makes it clear that, despite this change, personal data collected is transferred and processed in the United States where it is governed by United States law. While Flo does not sell identifiable user health data to third parties, the company’s privacy policy states it may still share user’s personal data “in response to subpoenas, court orders or legal processes . . . .” While the GDPR is one of the strongest international data privacy laws, it still does not provide United States users with much protection.

In the same update, Flo introduced “anonymous mode” letting users access the app without providing their name, email, or any technical identifiers. Flo said this decision was made “in an effort to further protect sensitive reproductive health information in a post-Roe America.” The FTC, however, states that claims of anonymized data are often deceptive and that the data is easily traceable. Users may still be at risk of potentially having their sensitive health data handed over to law enforcement. Further, research shows femtech apps often have significant shortcomings with respect to making privacy policies easy to read and that users are often unaware of what their consent means.

While femtech has the potential to provide much-needed attention to a group often under-researched and underrepresented in medicine, the need to enhance current data privacy standards should be at the forefront for developers, legislators, and regulators. Although femtech companies may be incentivized to sell sensitive health data, their resources may be better spent lobbying for the passage of legislation like the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (“ADPPA”) and My Body, My Data Act otherwise the lack of data privacy measures may turn users away from femtech altogether. While no current reports show that menstruating individuals are turning away from femtech apps, it may be too soon to tell the effects post-Dobbs.

The ADPPA is a bipartisan bill that would be the “first comprehensive information privacy legislation” and would charge the FTC with the authority to administer the Act. The ADPPA would regulate “sensitive covered data” including “any information that describes or reveals the past, present, or future physical health, mental health, disability, diagnosis, or healthcare condition or treatment of an individual” as well as “precise geolocation information.” ADPAA’s scope would extend beyond covered providers as defined by HIPAA and would encompass femtech apps. The ADPPA would reduce the amount of data available through commercial sources that is available to law enforcement and give consumers more rights to control their data. The Act, however, is not perfect, and some legislators have argued that it would make it more difficult for individuals to bring forth claims against privacy violations. While it is unlikely that Congress will pass or consider ADPAA before it convenes in January 2023, it marks a start to long-awaited federal privacy law discussions.

On a state level, California moved quickly to enact two bills that would strengthen privacy protections for individuals seeking abortion, including prohibiting cooperation with out-of-state law enforcement regardless of whether the individual is a California resident. Although California is working to become an abortion safe haven, abortion access is costly and individuals most impacted by the Supreme Court’s decision will likely not be able to fund trips to the state to take advantage of the strong privacy laws.

As menstruating individuals continue to navigate the post-Dobbs landscape, transparency from femtech companies should be provided to consumers with regard to how their reproductive health data is being collected and how it may be shared, especially when it comes to a growing healthcare service that individuals are exploring online - abortion pills.

Angela Petkovic is a second-year law student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

INTRODUCTION

“Zombies” may be pure fiction in Hollywood movies, but they are a very real concern in an area where most individuals would least expect – trademark law. A long-established doctrine in U.S. trademark law deems a mark to be considered abandoned when its use has been discontinued and where the trademark owner has no intent to resume use. Given how straightforward this doctrine seems, it is curious why the doctrine of residual goodwill has been given such great importance in trademark law.

Residual goodwill is defined as customer recognition that persists even after the last sale of a product or service have concluded and the owner has no intent to resume use. Courts have not come to a clear consensus on how much weight to assign to residual goodwill when conducting a trademark abandonment analysis. Not only is the doctrine of residual goodwill not rooted in federal trademark statutes, but it also has the potential to stifle creativity among entrepreneurs as the secondhand marketplace model continues to grow rapidly in the retail industry.

This dynamic has led to a phenomenon where (1) courts have placed too much weight on the doctrine of residual goodwill in assessing trademark abandonment, leading to (2) over-reliance on residual goodwill, which can be especially problematic given the growth of the secondhand retail market, and finally, (3) over-reliance on residual goodwill in the secondhand retail market will disproportionately benefit large corporations over smaller entrepreneurs.

A. The Over-Extension of Residual Goodwill in Trademark Law

A long-held principle in intellectual property law is that “[t]rademarks contribute to an efficient market by helping consumers find products they like from sources they trust.” However, the law has many forfeiture mechanisms that can put an end to a product’s trademark protection when justice calls for it. One of these mechanisms is the abandonment doctrine. Under this doctrine, a trademark owner can lose protection if the owner ceases use of the mark and cannot show a clear intent to resume use. Accordingly, the abandonment doctrine encourages brands to keep marks and products in use so that they cannot merely warehouse marks to siphon off market competition.

The theory behind residual goodwill is that trademark owners may deserve continued protection even after a prima facie finding of abandonment because consumers may associate a discontinued trademark with the producer of a discontinued product. This doctrine is primarily a product of case law rather than deriving from trademark statutes. Most courts will not rely on principles of residual goodwill alone in evaluating whether a mark owner has abandoned its mark. Instead, courts will often consider residual goodwill along with evidence of how long the mark had been discontinued and whether the mark owner intended to reintroduce the mark in the future.

Some courts, like the Fifth Circuit, have gone as far as completely rejecting the doctrine of residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analysis and will focus solely on the intent of the mark owner in reintroducing the mark. These courts reject the notion that a trademark owner’s “intent not to abandon” is the same as an “intent to resume use” when the owner is accused of trademark warehousing. Indeed, in Exxon Corp. v. Humble Exploration Co., the Fifth Circuit held that “[s]topping at an ‘intent not to abandon’ tolerates an owner’s protecting a mark with neither commercial use nor plans to resume commercial use” and that “such a license is not permitted by the Lanham Act.”

The topic of residual goodwill has gained increased importance over the last several years as the secondhand retail market has grown. The presence of online resale and restoration businesses in the fashion sector has made it much easier for consumers to buy products that have been in commerce for several decades and might contain trademarks still possessing strong residual goodwill. Accordingly, it will be even more crucial for courts and policymakers to take a hard look at whether too much importance is currently placed on residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analysis.

B. Residual Goodwill’s Increasing Importance Given the Growth of the Secondhand Resale Fashion Market

Trademark residual goodwill will become even more important for retail entrepreneurs to consider, given the rapid growth in the secondhand retail market. Brands are using these secondhand marketplaces to extend the lifecycles of some of their top products, which will subsequently extend the lifecycle of their intellectual property through increased residual goodwill.

Sales in the secondhand retail market reached $36 billion in 2021 and are projected to nearly double in the next five years to $77 billion. Major brands and retailers are now making more concerted efforts to move into the resale space to avoid having their market share stolen by resellers. As more large retailers and brands extend the lifecycle of their products through resale marketplaces, these companies will also likely extend the lifespan of their intellectual property based on the principles of residual goodwill. In other words, it is now more likely for residual goodwill to accrue with products that are discontinued by major brands and retailers now since those discontinued products are made available through secondhand marketplaces.

The impact of the secondhand retail market on residual goodwill analysis may seem like it is still in its early stages of development. However, the recent Testarossa case, Ferrari SpA v. DU , out of the Court of Justice of the European Union is a preview of what may unfold in the U.S. In Testarossa, a German toy manufacturer challenged the validity of Ferrari’s trademark for its Testarossa car model on the grounds that Ferrari had not used the mark since it stopped producing Testarossas in 1996. While Ferrari had ceased producing new Testarossa models in 1996, it had still sold $20,000 in Testarossa parts between 2011 and 2017. As a result, the CJEU ultimately ruled in Ferrari’s favor and held that production of these parts constituted “use of that mark in accordance with its essential function” of identifying the Testarossa parts and where they came from.

Although Ferrari did use the Testarossa mark in commerce by selling car parts associated with the mark, the court’s dicta in the opinion referred to the topic of residual goodwill and its potentially broader applications. In its reasoning, the CJEU explained that if the trademark holder “actually uses the mark, in accordance with its essential function . . . when reselling second-hand goods, such use is capable of constituting ‘genuine use.’”

The Testarossa case dealt primarily with sales of cars and automobile parts, but the implications of its ruling extend to secondhand retail, in general. If the resale of goods is enough to qualify as “genuine use” under trademark law, then this provides trademark holders with a much lower threshold to prove that they have not abandoned marks. This lower threshold for “genuine use” in secondhand retail marketplaces, taken together with how courts have given potentially too much weight to residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analyses, could lead to adverse consequences for entrepreneurs in the retail sector.

C. The Largest Brands and Retailers Will Disproportionately Benefit from Relaxed Trademark Requirements

The increasingly low thresholds for satisfying trademark “genuine use” and for avoiding trademark abandonment will disproportionately benefit the largest fashion brands and retailers at the expense of smaller entrepreneurs in secondhand retail. Retail behemoths, such as Nike and Gucci, will disproportionately benefit from residual goodwill and increasingly relaxed requirements for trademark protection since these companies control more of their industry value systems. This concept will be explained in more detail in the next section.

Every retail company is a collection of activities that are performed to design, produce, market, deliver, and support the sale of its product. All these activities can be represented using a value chain. Meanwhile, a value system includes both a firm’s value chain and the value chains of all its suppliers, channels, and buyers. Any company’s competitive advantages can be best understood by looking at both its value chain and how it fits into its overall value system.

In fashion, top brands and retailers, such as Nike and Zara, sustain strong competitive advantages in the marketplace in part because of their control over multiple aspects of their value systems. For example, by offering private labels, retailers exert control over the supplier portion of their value systems. Furthermore, by owning stores and offering direct-to-consumer shipping, brands exert control over the channel portion of their value systems. These competitive advantages are only heightened when a company maintains tight protection over their intellectual property.

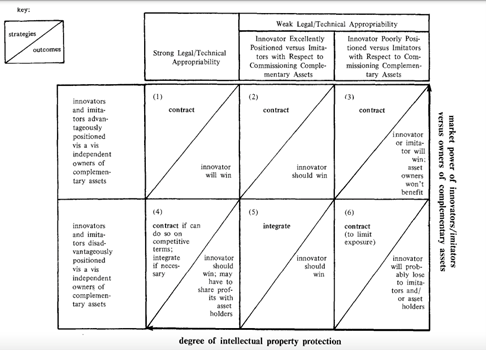

As portrayed in the figure below , companies maintain the strongest competitive advantages in cell one when they are advantageously positioned relative to owners of complementary assets, and they maintain strong intellectual property protection. In such situations, an innovator will win since it can derive value at multiple sections of its value system using its intellectual property.

CONCLUSION

Although there is little case law on the relevance of residual goodwill and secondhand retail marketplaces, it is only a matter of time until the largest fashion brands and retailers capitalize on increasingly low thresholds for demonstrating trademark “genuine use.” Courts and policymakers should now stay alert of these potential issues when dealing with trademark abandonment matters.

Rohun Reddy is a third-year JD-MBA student at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

In August 2020, Marlene Stollings, the head coach of Texas Tech Women’s Basketball Team, allegedly forced her players to wear heart rate monitors during practice and games. Stollings would subsequently view the player data and reprimand each player who did not achieve their target heart rates. It could be argued that Stollings was simply pushing her players to perform better, however former player Erin DeGrate described Stollings’ use of the data as a “torture mechanism.” This is just one reported example of how athletic programs use athlete data collected from wearable technology to the student athlete’s detriment.

As of 2021 the market for wearable devices in athletics has a $79.94 billion valuation and is expected to grow to $212.67 billion by 2029. The major market competitors in the industry consist of Nike, Adidas, Under Armour, Apple, and Alphabet, Inc. so the expected growth comes as no surprise. Some wearable technology is worn by everyday consumers to simply track how many calories they have burned in a day or whether they met their desired exercise goals. On the other hand, professional and college athletes use wearable technology to track health and activity data to better understand their bodies and gain a competitive edge. While professional athletes can negotiate which types of technology they wear and how the technology is used through their league’s respective collective bargaining agreement, collegiate athletes do not benefit from these negotiation powers. Universities ultimately possess a sort of “constructive authority” to determine what kind of technology students wear, what data is collected, and how that data is used without considering the student athlete’s level of comfort. This is because if the student-athlete chooses to-opt out of wearable technology usage it may hinder their playing time or lead to being kicked off the team.

Studies show that collecting athlete biometric data has a positive effect on a player’s success and helps reduce possible injury. For instance, professional leagues utilize wearables for creating heat maps to analyze an athlete’s decision-making abilities. The Florida State Seminole basketball program also routinely uses wearables to track and monitor early signs of soft tissue damage which helped reduce the team’s overall injury rate by 88%. However, there are significant trade-offs including the invasion of an athlete’s privacy and possible misuse of the data.

Section I of this article will examine the different types of information collected from athletes and how that information is being collected. Section II will discuss a college athlete’s right to privacy under state biometric laws. Section III will discuss how data privacy laws are changing with respect to collecting athlete biometric data. Last, section IV will discuss possible solutions to collecting biometric data.

II. What Data is Collected & How?

Many people around the country use Smart Watch technology such as Fitbits, Apple Watches, or Samsung Galaxy Watches to track their everyday lifestyle. Intending to maintain a healthy lifestyle, people usually allow these devices to monitor the number of steps taken throughout the day, how many calories were burned, the variance of their heart rate, or even their sleep schedule. On the surface, there is nothing inherently problematic about this data collection, however, biometric data collected on college athletes is much more intrusive. Athletic programs are beginning to enter into contractual relationships with big tech companies to provide wearable technology for their athletes. For example, Rutgers University football program partnered with Oura to provide wearable rings for their athletes. Moreover, the types of data these devices collect include blood oxygenation levels, glucose, gait, blood pressure, body temperature, body fatigue, muscle strain, and even brain activity. While many college athletes voluntarily rely on wearable technology to develop a competitive edge, some collegiate programs now mandate students wear the technology for the athletic program to collect the data. Collegiate athletes do not have the benefit of negotiations or the privileges of a collective bargaining agreement, but the athletes do sign a national letter of intent which requires a waiver of certain rights in order to play for the University. Although college athletes have little to no bargaining power, they should be given the chance to negotiate this national letter of intent to incorporate biometric data privacy issues because it is ultimately their bodies producing the data.

II. Biometric Privacy Laws

Currently, there are no federal privacy laws on point that protect collecting student athlete biometric data. Nonetheless, some states have enacted biometric privacy statutes to deal with the issue. Illinois, for example, which houses thirteen NCAA Division I athletic programs, authorized the Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA) in 2008. BIPA creates standards for how companies in Illinois must handle biometric data. Specifically, BIPA prohibits private companies from collecting biometric data unless the company (1) informs the individual in writing that their biometric data is being collected or stored, (2) informs the individual in writing why the data is being collected along with the duration collection will continue for and (3) the company receives a written release from the individual. This is a step in the right direction in protecting athletes’ privacy since the statute’s language implies athletes would have to provide informed consent before their biometric data is collected. However, BIPA does not apply to universities and their student-athletes since they fall under the 25(c) exemption for institutions. Five other Illinois courts, including a recent decision in Powell v. DePaul University, explain the 25(c) exemption extended to “institutions of higher education that are significantly engaged in financial activities such as making or administering student loans.”

So, although Illinois has been praised for being one of the first states to address the emerging use of biometric data by private companies, it does not protect collegiate athletes who are “voluntarily” opting into the wearable technology procedures set by their teams.

III. Data Collection Laws are Changing

While BIPA does not protect collegiate athletes, other states have enacted privacy laws that may protect student-athletes. In 2017 the state of Washington followed Illinois’ footsteps by enacting its own biometric privacy law that is substantively similar to the provisions in BIPA. But the Washington law contains an expanded definition of what constitutes “biometric data.” Specifically, the law defines biometric identifiers as “data generated by automatic measurements of an individual’s biological characteristics, such as a fingerprint, voiceprint, eye retinas, irises or other unique biological patterns or characteristics that are used to identify a specific individual.” By adding the two phrases, “data generated by automatic measurements of an individual’s biological characteristics,” and “other biological patterns or characteristics that is used to identify a specific individual,” the Washington law may encompass the complex health data collected from student-athletes. The language in the statute is broad and thus likely covers an athlete’s biometric data because it is unique to that certain individual and could be used as a characteristic to identify that individual.

IV. Possible Solutions to Protect Player Biometric Data

Overall, it’s hard to believe that biometric data on student-athletes will see increased restrictions any time soon. There is too much on the line for college athletic programs to stop collecting biometric data since programs want to do whatever it takes to gain a competitive edge. Nonetheless, it would be possible to restrict who has access to athletes’ biometric data. In 2016, Nike and the University of Michigan signed an agreement worth $170 million where Nike would provide Michigan athletes with apparel and in return, Michigan would allow Nike to obtain personal data from Michigan athletes through the use of wearable technology. The contract hardly protected the University’s student-athletes and was executed in secrecy seeing its details were only revealed after obtaining information through the Freedom of Information Act. Since the University was negotiating the use of the student athlete’s biometric data on the athlete’s behalf, it can likely be assumed that the University owns the data. Therefore, athletes should push for negotiable scholarship terms allowing them to restrict access to their biometric data and only allow the athletic program’s medical professionals to obtain the data.

One would think that HIPAA protects this information from the outset. Yet there is a “general consensus” that HIPAA does not apply to information collected by wearables since (a) “wearable technology companies are not considered ‘covered entities’, (b) athletes consent to these companies having access to their information, or (c) an employment exemption applies.” Allowing student-athletes to restrict access before their college career starts likely hinders the peer pressure received from coaches to consent to data collection. Further, this would show they do not consent to companies having access to their information and could trigger HIPAA. This would also cause the information to be privileged since it is in the hands of a medical professional, and the athlete could still analyze the data with the medical professional on his or her own to gain the competitive edge biometric data provides.

Anthony Vitucci is a third-year law student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

The development of AI systems has reached a point at which these systems can create and invent new products and processes just as humans can. There are several features of these AI systems that allow them to create and invent. For example, the AI systems imitate intelligent human behavior, as they can perceive data from outside and decide which actions to take to maximize their probability of success in achieving certain goals. The AI systems can also evolve and change based on new data and thus may produce results that the programmers or operators of the systems did not expect in their initial plans. They have created inventions in different industries, including the drug, design, aerospace, and electric engineering industries. NASA’s AI software has designed a new satellite antenna, and Koza’s AI system has designed new circuits. Those inventions would be entitled to patent protection if developed by humans. However, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has refused to assign the patent rights of these inventions to the AI systems.

The USTPO Denies Patent Rights to AI Systems

In a patent application that listed an AI system, DABUS, as the inventor, the USPTO refused to assign the patent right to DABUS and thus denied the patent application. DABUS invented an emergency warning light and a food container. The USPTO based its decision mainly upon a plain reading of the relevant statutes. 35 U.S.C § 115(a) states that “[a]n application for patent that is filed … shall include, or be amended to include, the name of the inventor for any invention claimed in the invention.” 35 U.S.C § 100(a) defines an “inventor” as “the individual, or if a joint invention, the individuals collectively who invented or discovered the subject matter of the invention.” 35 U.S.C § 115 consistently refers to inventors as natural persons, as it uses pronouns specific to natural persons, “himself” and “herself.” 35 U.S.C § 115 further states that the inventor must be a person who can execute an oath or declaration. The USPTO thus refused to extend its interpretation of “inventor” to an AI system, and it has stated that “interpreting ‘inventor’ broadly to encompass machines would contradict the plain reading of the patent statutes that refer to persons and individuals.

The Federal Circuit follows the same approach. In Beech Aircraft Corp. v. EDO Corp., the Federal Circuit held that “only natural persons can be ‘inventors.’” Therefore, in the current U.S. legal system, patent rights cannot be assigned for AI-generated inventions even though such inventions would be entitled to patent protection had they been created by humans.

Decisions regarding the patent protection for AI-generated inventions have spurred some disputes among academics. The creator of DABUS, Stephen Thaler, insisted that the inventions created by DABUS should be entitled to patent protection because DABUS is a system that can devise and develop new ideas, unlike some traditional AI systems that can only follow fixed plans. Stephen Thaler contends that DABUS has not been trained using data that is relevant to the invention it produced. Therefore, he claims, that DABUS independently recognized the novelty and usefulness of its instant inventions, entitling its invention patent protection. Thaler also raises an argument regarding the moral rights of inventions. Although current U.S. patent law may recognize Thaler as the inventor of these inventions, he emphasizes that recognizing him rather than DABUS as the inventor devalues the traditional human inventorship by crediting a human with work that they did not invent.

Some legal academics support the contentions of Stephen Thaler. For example, Professor Ryan Abbott agrees that AI systems should be recognized as inventors and points out that if in the future, using AI becomes the prime method of invention, the whole IP system will lose its effectiveness.

However, there are also objections to Thaler’s contentions. For example, AI policy analyst Hodan Omaar disagrees that AI systems should be granted inventor status because she believes that the patent system is for protecting an inventor’s economic rights, not their moral rights. She points out that the primary goal of patent law is to promote innovations, but Thaler’s proposed changes to patent law do little to do so. She argues that the value of protecting new inventions is for a patent owner rather than an inventor, which means that it makes no difference who creates the value. Thus, she concludes that listing DABUS as inventor makes no difference to the patent system. Omaar further argues that the proposed changes would introduce a legally unpunishable inventor that threatens human inventors, because the government cannot effectively hold AI systems, unlike individuals or corporations, directly accountable if they illegally infringe on the IP rights of others.

Patent Rights to AI Systems in Other Jurisdictions and Insights on U.S. Patent Law

Some foreign jurisdictions take the same stance as the United States. The UK Court of Appeal recently refused to grant patent protection to the inventions generated by DABUS because the Court held that patent law in the UK requires an inventor to be a natural person.

Despite failing to in the US and UK, Thaler succeeded in getting patent protections for the inventions created by DABUS in some other jurisdictions that allowed listing DABUS as the inventor. South Africa granted patent protection to a food container invention created by DABUS. This is the first patent for an AI-generated invention that names an AI system as the inventor. The decision may be partially explained by the recent policy landscape of South Africa, as its government wants to solve the country’s socio-economic issues by increasing innovation.

Thaler gained another success in Australia. While the decision in South Africa was made by a patent authority, the decision in Australia is the first decision of this type made by a court. The Commissioner of Patents in Australia rejected the patent application by Thaler, but the Federal Court of Australia then answered the key legal questions in favor of permitting AI inventors. Unlike patent law in the US, the Australian Patents Act does not define the term “inventor.” The Commissioner of Patents contended that the term “inventor” in the Act only refers to a natural person. However, Thaler successfully argued to the Court that the ordinary meaning of “inventor” is not limited to humans. The Court noted that there is no specific aspect of patent law in Australia that does not permit non-human inventors.

Examining the different decisions regarding the patent application of DABUS in different jurisdictions, we can see that the different outcomes may result from different policy landscapes and different patent law provisions in different jurisdictions.

For example, South Africa has a policy landscape where it wants to increase innovation to solve its socio-economic issues, while in the U.S., the government may not have the same policy goals related to patent law. Australia’s patent law does not limit an “inventor” to mean a natural person, while U.S. patent law specifically defines the word “inventor” to exclude non-human inventors in this definition. Thus, it is reasonable for U.S. patent law not to grant patent rights to AI-systems for AI-generated inventions, unless the legislature takes actions to broaden the definition of “inventor” to include non-human inventors.

The primary goal of the U.S. patent law is to promote innovation. If those who want to persuade the U.S. legislature to amend the current patent law to allow non-human inventors cannot demonstrate that such a change is in line with that primary goal, then it is unlikely that the legislature would support such a change. Whether granting patents to AI systems and allowing those systems to be inventors can promote innovation is likely to be an ongoing debate among academics.

Jason Chen is a third-year law student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

If nothing else, Facebook’s recent announcement that it plans to change its name to “Meta” is a sign that the metaverse is coming and that our legal system must be prepared for it. As the metaverse, the concept of a virtual version of the physical world, gains increased popularity, individuals will engage in more transactions involving non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, to purchase the virtual items that will inhabit metaverse worlds. Accordingly, the United States will need more robust regulatory frameworks to deal with NFT transactions, especially in the gaming industry, where NFT use will likely rise significantly.

In most other areas of digital media and entertainment, NFTs are often associated with niche items, such as high-priced autographs and limited-edition collectibles. However, in the video gaming sector, existing consumer spending habits on rewards such as loot boxes, cosmetic items, and gameplay advantages provide fertile ground for explosive growth in NFT use. This article will explore the outlook for NFTs in gaming, why gaming NFT creators should consider the potential impact of financial regulations on their tokens, and how current U.S. financial regulations could apply to this ownership model.

A. Current State of Virtual Currencies and Items in Gaming

Gaming has long been the gateway for consumers to explore immersive digital experiences, thus explaining why virtual currencies and collectible items have such strong roots in this sector. Further, given the popularity of virtual currencies and collectibles in gaming, it is no surprise that cryptocurrencies and NFTs have similarly experienced success in this space.

NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, are unique digital assets that consumers may purchase with fiat currency or cryptocurrency. NFTs can be “minted” for and linked to almost any digital asset (e.g., video game items, music, social media posts), and even many physical assets. While NFTs are blockchain-based just like cryptocurrencies, the key difference between the two is that a NFT is not mutually interchangeable with any other NFT (i.e. they are non-fungible). So why are they so special? As digital experiences continue to move to the metaverse, NFTs will serve as a primary means for consumers to connect with companies, celebrities, and, eventually, each other.

In the simplest explanation, metaverse is the concept of a digital twin of the physical world, featuring fully interconnected spaces, digital ownership, virtual possessions, and extensive virtual economies. Mainstream media has already given significant coverage to metaverse activities that have appeared in popular games, such as concerts in Fortnite and weddings in Animal Crossing. However, more futuristic examples of how NFTs and metaverse could transform our daily lives exist in the Philippines with Axie Infinity and Decentraland, a blockchain-based virtual world.

In Axie Infinity, players breed, raise, battle, and trade digital animals called Axies. The game was launched in 2018, but it took off in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic as many families used it to supplement their income or make several times their usual salary. To date, the game has generated $2.05 billion in sales. Meanwhile, plots of virtual land in Decentraland, a 3D virtual world where consumers may use the Etheruem blockchain to purchase virtual plots of lands as NFTs, are already selling for prices similar to those offered in the physical world. For example, in June 2021, a plot of land in the blockchain-based virtual world sold for $900,000.

The growth in popularity of Axie Infinity has already caught the eye of the Philippine Bureau of Internal Revenue, which has announced that Axie Infinity players must register to pay taxes. As financial regulation of NFTs looms, it will be imperative for U.S. gaming companies to consider how federal courts and the government will recognize the status of NFTs.

B. Financial Regulation and NFTs

As NFT transaction volume grows, there will undoubtedly be greater scrutiny over these transactions by financial regulators. While the current legal and regulatory environment does not easily accommodate virtual assets, there are a two primary ways NFTs may be regulated.

1. Securities Regulation

One of the most hotly discussed legal issues concerning NFTs involves whether these tokens should be recognized as securities. Under SEC v. W.J. Howey Co., a transaction is deemed an investment contract under the Securities Act where all of the following four factors are satisfied: (1) an investment of money; (2) in a common enterprise; (3) with a reasonable expectation of profits; (4) to be derived from the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others.

Intuitively, NFTs, in the form of virtual collectible items, don’t seem like traditional tradable securities as they are unique, non-fungible items. Indeed, they do not appear to demonstrate the type of “horizontal commonality” that federal courts have held to be necessary to satisfy the “common enterprise” aspect of the Howey test. “Horizontal commonality” is generally understood to involve the pooling of money or assets from multiple investors where the investors share in the profits and risk.

However, the Securities Exchange Commission has stated that it “does not require vertical or horizontal commonality per se, nor does it view a ‘common enterprise’ as a distinct element of the term ‘investment contract.’” Therefore, the fungibility aspect of the token alone may not preclude it from inclusion under securities regulation.

A more interesting inquiry might involve assessing whether the reasonable expectation of profits associated with an NFT is based on the “efforts of [others],” as outlined in Howey. In evaluating this element of the Howey test, the SEC considers whether a purchaser reasonably expects to rely on the efforts of active participants and whether those efforts are “undeniably significant” and “affect the failure or success of the enterprise.” Under this lens, how an NFT is offered and sold is critical to consider.

For example, if one mints (i.e., creates a NFT for) a piece of graphic art that sits and passively accumulates value, the failure or success of purchasing such a NFT would likely not be highly reliant on the activities of others. As the SEC has noted, price appreciation resulting solely from external market forces (such as general inflationary trends or the economy) impacting the supply and demand for an underlying asset generally is not considered ‘profit’ under the Howey test. Similarly, if a consumer purchases a digital pet, like those in Axie Infinity, that actively accumulates value through winning a series of battles, the success or failure of this digital pet would also not be highly reliant on the activities of others. However, this analysis becomes more complex when considering the recent increased interest in “fractional NFTs,” or “f-NFTs”, where an investor shares a partial interest in an NFT with others. Since these fractional interests are more accessible to a larger number of smaller investors, they may be more likely to drive market trading and, as such, be recognized as securities.

2. Federal Anti-Money Laundering Statutes

Under the Bank Secrecy Act, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or “FinCEN,” is the U.S. Department of Treasury bureau that has the authority to regulate financial systems to fight money laundering. Although it has yet to comment directly on NFTs, FinCEN has released guidance suggesting that the movement of monetary value through virtual currencies could trigger money transmission regulations.

A critical factor determining whether the transfer of an NFT is a money transmission service will be whether FinCEN recognizes the NFT as “value that substitutes for currency.” If the NFT’s value may be substituted for currency then the transfer of such a NFT would likely trigger money transmission regulations. If players can purchase NFTs using a virtual currency that can cash out for fiat currency, then this transfer may be subject to FinCEN regulation. Alternatively, based on FinCEN’s recent guidance, even if NFTs are purchased with virtual currency that users cannot cash out for fiat currency, money transmission regulation may be triggered. Indeed, depending on how the gaming platform facilitates the transfer of in-game currency, regulatory risks may exist when users purchase third-party goods or make virtual marketplace transactions.

Earlier this year, Congress took a significant step towards making money transmission regulations more inclusive of NFT use cases when it passed the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020. Under the Act, art and antiquities dealers are now subject to the same anti-money laundering regulations that previously applied to financial institutions under the Bank Secrecy Act. This development will undoubtedly have a significant impact on the potential liability that gaming platforms can face as “dealers” of NFTs.

Conclusion

The United States is still a long way away from having laws that adequately regulate the creation, selling, and purchase of NFTs. However, NFT usage continues to increase rapidly. Nearly half of all U.S. adults are interested in participating in the NFT market, and gamers are 2.6x more likely to participate in the NFT market. As regulators move quickly to keep up with the pace of this market, firms will need to stay alert to ensure that they maintain regulatory compliance.

Rohun Reddy is a third-year JD-MBA student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law and Kellogg School of Management.