Category: Uncategorized

If nothing else, Facebook’s recent announcement that it plans to change its name to “Meta” is a sign that the metaverse is coming and that our legal system must be prepared for it. As the metaverse, the concept of a virtual version of the physical world, gains increased popularity, individuals will engage in more transactions involving non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, to purchase the virtual items that will inhabit metaverse worlds. Accordingly, the United States will need more robust regulatory frameworks to deal with NFT transactions, especially in the gaming industry, where NFT use will likely rise significantly.

In most other areas of digital media and entertainment, NFTs are often associated with niche items, such as high-priced autographs and limited-edition collectibles. However, in the video gaming sector, existing consumer spending habits on rewards such as loot boxes, cosmetic items, and gameplay advantages provide fertile ground for explosive growth in NFT use. This article will explore the outlook for NFTs in gaming, why gaming NFT creators should consider the potential impact of financial regulations on their tokens, and how current U.S. financial regulations could apply to this ownership model.

A. Current State of Virtual Currencies and Items in Gaming

Gaming has long been the gateway for consumers to explore immersive digital experiences, thus explaining why virtual currencies and collectible items have such strong roots in this sector. Further, given the popularity of virtual currencies and collectibles in gaming, it is no surprise that cryptocurrencies and NFTs have similarly experienced success in this space.

NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, are unique digital assets that consumers may purchase with fiat currency or cryptocurrency. NFTs can be “minted” for and linked to almost any digital asset (e.g., video game items, music, social media posts), and even many physical assets. While NFTs are blockchain-based just like cryptocurrencies, the key difference between the two is that a NFT is not mutually interchangeable with any other NFT (i.e. they are non-fungible). So why are they so special? As digital experiences continue to move to the metaverse, NFTs will serve as a primary means for consumers to connect with companies, celebrities, and, eventually, each other.

In the simplest explanation, metaverse is the concept of a digital twin of the physical world, featuring fully interconnected spaces, digital ownership, virtual possessions, and extensive virtual economies. Mainstream media has already given significant coverage to metaverse activities that have appeared in popular games, such as concerts in Fortnite and weddings in Animal Crossing. However, more futuristic examples of how NFTs and metaverse could transform our daily lives exist in the Philippines with Axie Infinity and Decentraland, a blockchain-based virtual world.

In Axie Infinity, players breed, raise, battle, and trade digital animals called Axies. The game was launched in 2018, but it took off in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic as many families used it to supplement their income or make several times their usual salary. To date, the game has generated $2.05 billion in sales. Meanwhile, plots of virtual land in Decentraland, a 3D virtual world where consumers may use the Etheruem blockchain to purchase virtual plots of lands as NFTs, are already selling for prices similar to those offered in the physical world. For example, in June 2021, a plot of land in the blockchain-based virtual world sold for $900,000.

The growth in popularity of Axie Infinity has already caught the eye of the Philippine Bureau of Internal Revenue, which has announced that Axie Infinity players must register to pay taxes. As financial regulation of NFTs looms, it will be imperative for U.S. gaming companies to consider how federal courts and the government will recognize the status of NFTs.

B. Financial Regulation and NFTs

As NFT transaction volume grows, there will undoubtedly be greater scrutiny over these transactions by financial regulators. While the current legal and regulatory environment does not easily accommodate virtual assets, there are a two primary ways NFTs may be regulated.

1. Securities Regulation

One of the most hotly discussed legal issues concerning NFTs involves whether these tokens should be recognized as securities. Under SEC v. W.J. Howey Co., a transaction is deemed an investment contract under the Securities Act where all of the following four factors are satisfied: (1) an investment of money; (2) in a common enterprise; (3) with a reasonable expectation of profits; (4) to be derived from the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others.

Intuitively, NFTs, in the form of virtual collectible items, don’t seem like traditional tradable securities as they are unique, non-fungible items. Indeed, they do not appear to demonstrate the type of “horizontal commonality” that federal courts have held to be necessary to satisfy the “common enterprise” aspect of the Howey test. “Horizontal commonality” is generally understood to involve the pooling of money or assets from multiple investors where the investors share in the profits and risk.

However, the Securities Exchange Commission has stated that it “does not require vertical or horizontal commonality per se, nor does it view a ‘common enterprise’ as a distinct element of the term ‘investment contract.’” Therefore, the fungibility aspect of the token alone may not preclude it from inclusion under securities regulation.

A more interesting inquiry might involve assessing whether the reasonable expectation of profits associated with an NFT is based on the “efforts of [others],” as outlined in Howey. In evaluating this element of the Howey test, the SEC considers whether a purchaser reasonably expects to rely on the efforts of active participants and whether those efforts are “undeniably significant” and “affect the failure or success of the enterprise.” Under this lens, how an NFT is offered and sold is critical to consider.

For example, if one mints (i.e., creates a NFT for) a piece of graphic art that sits and passively accumulates value, the failure or success of purchasing such a NFT would likely not be highly reliant on the activities of others. As the SEC has noted, price appreciation resulting solely from external market forces (such as general inflationary trends or the economy) impacting the supply and demand for an underlying asset generally is not considered ‘profit’ under the Howey test. Similarly, if a consumer purchases a digital pet, like those in Axie Infinity, that actively accumulates value through winning a series of battles, the success or failure of this digital pet would also not be highly reliant on the activities of others. However, this analysis becomes more complex when considering the recent increased interest in “fractional NFTs,” or “f-NFTs”, where an investor shares a partial interest in an NFT with others. Since these fractional interests are more accessible to a larger number of smaller investors, they may be more likely to drive market trading and, as such, be recognized as securities.

2. Federal Anti-Money Laundering Statutes

Under the Bank Secrecy Act, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or “FinCEN,” is the U.S. Department of Treasury bureau that has the authority to regulate financial systems to fight money laundering. Although it has yet to comment directly on NFTs, FinCEN has released guidance suggesting that the movement of monetary value through virtual currencies could trigger money transmission regulations.

A critical factor determining whether the transfer of an NFT is a money transmission service will be whether FinCEN recognizes the NFT as “value that substitutes for currency.” If the NFT’s value may be substituted for currency then the transfer of such a NFT would likely trigger money transmission regulations. If players can purchase NFTs using a virtual currency that can cash out for fiat currency, then this transfer may be subject to FinCEN regulation. Alternatively, based on FinCEN’s recent guidance, even if NFTs are purchased with virtual currency that users cannot cash out for fiat currency, money transmission regulation may be triggered. Indeed, depending on how the gaming platform facilitates the transfer of in-game currency, regulatory risks may exist when users purchase third-party goods or make virtual marketplace transactions.

Earlier this year, Congress took a significant step towards making money transmission regulations more inclusive of NFT use cases when it passed the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020. Under the Act, art and antiquities dealers are now subject to the same anti-money laundering regulations that previously applied to financial institutions under the Bank Secrecy Act. This development will undoubtedly have a significant impact on the potential liability that gaming platforms can face as “dealers” of NFTs.

Conclusion

The United States is still a long way away from having laws that adequately regulate the creation, selling, and purchase of NFTs. However, NFT usage continues to increase rapidly. Nearly half of all U.S. adults are interested in participating in the NFT market, and gamers are 2.6x more likely to participate in the NFT market. As regulators move quickly to keep up with the pace of this market, firms will need to stay alert to ensure that they maintain regulatory compliance.

Rohun Reddy is a third-year JD-MBA student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law and Kellogg School of Management.

When Meta’s services went down this past October, users were unable to access all of Meta’s applications, including Instagram, Messenger, and WhatsApp. This digital outage had physical consequences, as some Meta employees got locked out of their offices. The effects rippled outside of Meta’s own ecosystem, as some consumers soon discovered they were unable to log in to shop on select e-commerce websites, while others quickly found out that they could no longer access the accounts used to control their smart TVs or smart thermostats. Drawn by the ease of using Facebook accounts to log into websites, users had come to allow their Facebook account to act as a kind of digital identity. The outage, along with revelations from a fortuitously timed whistleblower, reminded users just how much individuals and governments depend on the “critical infrastructure” Facebook provides. Lawmakers in the U.S. have struggled with the question of how Meta should be regulated, or how its power should be reined in. One step towards mitigating Meta’s power would be to develop alternative digital Identity Management (“IdM”) systems.

The Legal Role of Identification

Technology has been used to verify identity for hundreds of years. Back in the third century B.C.E., fingerprints, recorded in wax, were used to authenticate written documents. For centuries, identification technology has allowed strangers to bridge a “trust gap” by authenticating and authorizing.[1]

In the present day, IdM systems have become a critical piece of technology for governments, allowing for the orderly provision of a range of services, like healthcare, voting, and education. IdM systems are also critical for the individual, because they allow a person to “prove[] one’s status as a person who can exercise rights and demand protection under the law.” The UN went so far as to describe an individual’s ability to prove a legal identity as a “fundamental and universal human right.”

Currently, there are over one billion people who live in the “identity gap” and cannot prove their legal identity. Put another way, one billion people lack a fundamental, universal human right. What makes this issue more pernicious is that the majority of individuals in the identity gap are women, children, stateless individuals and refugees. The lack or loss of legal identity credentials is correlated with increased risk for displacement, underage marriage, and child trafficking. Individuals living in the “identity gap” face significant barriers to receiving “basic social opportunities.”

Identity in Digital Age

The legal and social issues created by the “identity gap” are now evolving. In addition to the individuals who can’t prove their legal identity at all, there are over 3.4 billion people who have a legally recognized identification, but cannot use that identification in the digital world.

A 2017 European Commission Report found that an individual’s ability to have a digital identity “verg[es] on a human right.” The report then argued that one of the deep flaws of the internet is that there is no reliable, secure method to identify people online. The New York Times called this “one of biggest failures of the… internet.” Still, proving digital identity isn’t just a human rights issue; it’s also critical for economic development. A McKinsey report posited that a comprehensive digital IdM system would “unlock economic value equivalent to 3 to 13 percent of GDP in 2030.”

Digital IdM systems, however, are not without risk. These systems are often developed in conjunction with biometric databases, creating systems that are “ripe for exploitation and abuse.”

IdM Systems

Centralized

The most common IdM scheme is a “centralized” system; in a centralized IdM scheme, a single entity is responsible for issuing and maintaining the identification and corresponding information. In centralized IdM schemes, identity is often linked to a certain benefit or right. One popular example in the United States is the Social Security Number (“SSN”); SSNs are issued by the Social Security Administration, who then use that number to maintain information about what social security benefits an individual is eligible to receive. Having an SSN is linked to the right to participate in the social security system.

The centralized IdM schemes typically verify identity in one of two ways: via a physical and anti-forgery mechanism or a registry. These systems have proved remarkably resilient for a few reasons. They are easily stored for long periods of times and can be easily presented for many different kinds of purposes. Still, both ways have shortcomings, including function creep[2] and lack of security.

Identity systems that rely on anti-forgery mechanisms, like signatures, watermarks, or special designs, can also have security flaws. First, these documents require the checking party to validate every anti-forgery mechanism; this might require high levels of skill, time, or expertise. Additionally, once a physical identification is issued, the issuing party is generally unable to revoke or control the information. Finally, anti-forgery measures constantly need to be updated because parties have great incentives to create fake documents.

Another security shortcoming of centralized IdM systems is that they rely on registries to contain all their data. Registries are problematic because they have a single point of failure. If one registry is compromised, an entire verification system can be undone. For instance, if SSNs became public, the SSN would become worthless; the value is in the secrecy.

Equally significant is the possibility of function creep, which can happen when a user loses control of their identification. SSNs, for example, were designed for a single purpose: the provisioning of social security benefits. Now, SSNs serve as a ubiquitous government identifier that is “now used far beyond its original purpose.” This is problematic because SSNs contain “no authenticating information” and can easily be forged. It’s not just governments, however, that allow function creep in centralized IdM systems. This happens for privately managed identity systems as well, as the Facebook hack showed.

The Alternatives: Individualistic and Federated IdM Models

Another type of IdM system is an individualistic or “user-centric” system. The goal of these systems is to allow the user to have “full control of all the transactions involving [their] identity” by requiring a user’s explicit approval of how their identity data is released and shared. Unlike those in “centralized” schemes, these types of identification do not grant any inherent rights. Instead, they give individuals the ability to define, manage, and prove their own identity.

To date, technical hurdles have prevented the widespread adoption of these “user-centric” systems. Governments and private companies alike have proposed using blockchain to create IdM systems that allow individuals to access their own data “without the need of constant recourse to a third-party intermediary to validate such data or identity.” There is hope that blockchain can provide the technical support to create an “individualist” IdM system that is both secure and privacy-friendly. Still, these efforts are in their infancy.

The last major type of IdM system is a federated model. Federated IdM systems require a high degree of cooperation between identity providers and service providers; the benefit is single sign on (SSO) capabilities whereby a user can use their credentials from one site to access other sites. This is similar to the Facebook model of “identity.” The lynchpin of any such system, however, is who the “trusted external party,” who acts as the verifier, is. The risk is that these systems lack transparency, meaning users might not know how their data is used.

Conclusion

Using Facebook to verify identity online is quick and easy. Yet this system is inadequate. An individual’s ability to state, verify, and prove their digital identity will be “the key to survival,” particularly given how difficult it is to create trust in the digital space. Proving identity is a technical problem, but this technical problem is closely linked with an individual’s ability to act as a citizen, in person or online. Governments and corporations alike have recognized the importance of improved digital identity systems and have begun advocating for more standardized identity systems. Detractors of digital identification systems argue that an individual’s identity should not depend on the conferral of documents by a third party, and that relying on these types of documents is contrary to the idea that humans have inherent rights. They’ll then quickly point to examples of authoritarian governments who use identity tracking for evil purposes. These criticisms ignore the reality that proving identification is already an essential part of life and that many rights are only conferred when you have the proper identification. Further, these criticisms fail to recognize that superior identification systems will provide benefits that will accrue to society as a whole. They could be used to record vaccination status, fight identity fraud, or even to create taxation systems based on consumption.

Identification and identity are closely linked. As we transition towards even more digital services, taking steps to ensure that we have control over our digital identity will be more than a technology or privacy problem. Our ability to have and control our identity will continue to be a key driver of social and economic mobility.

[1] In this context, authentication is the ability to prove that a user is who they say they are, and an authorization function shows that the user has the rights to do what they’re asking to do.

[2] Function creep is when a piece of information or technology is used for more purposes than it was originally intended.

Henry Rittenberg is a 2nd year student in Northwestern’s JD-MBA program.

When a musician desires to record a cover version of a song (i.e., their own version of a song written or made famous by someone else), the process for obtaining the rights to do so is quite simple: they obtain a mechanical license—a compulsory license that can be obtained by paying the appropriate fee to the copyright holder or their representative—but only after the copyright holder has exercised their right of first publishing. And that’s all there is to it. The artist records their version of the song, releases it into the world, pays royalties to the copyright holder, and, so long as they have abided by all the aforementioned steps, they likely do not run into any issues relating to this process. This process is simple, but in a time where musicians liberally borrow material from others and the resulting songwriting credits read like novellas, it creates issues in a discrete subset of cases.

17 USC § 115(a)(2) provides that

A compulsory license includes the privilege of making a musical arrangement of the work to the extent necessary to conform it to the style or manner of interpretation of the performance involved, but the arrangement shall not change the basic melody or fundamental character of the work, and shall not be subject to protection as a derivative work under this title, except with the express consent of the copyright owner.

Under this provision, arrangements of musical works prepared under mechanical licenses do not receive copyright protection unless expressly granted by the copyright holder. For most musicians preparing recordings under this type of license, this is not a very concerning issue—they still retain a copyright in their sound recording, and they are likely to be the only users of their arrangement. But consider the following situation:

- An artist obtains a mechanical license in order to record a cover of a song.

- They write a new arrangement of the song, with additional musical ideas not present in the original arrangement of the song.

- They are unsuccessful in their attempts to gain the copyright owner’s consent for the arrangement to receive its own copyright protection.

- They record the song, using their new arrangement, and release the recording.

- Some time later, another artist writes a song which repurposes the aforementioned musical ideas present only in the arrangement prepared under the mechanical license.

What happens here? The arrangement is not provided copyright protection, but the new artist has to credit someone for the ideas that they repurposed in their new song. So, the songwriting credit for the portion borrowed goes to the original songwriters, even though they were not involved in writing the particular musical ideas.

Consider the following real-life example in order to understand the strange results that occur in these situations. In 1979, “And the Beat Goes On” was released by The Whispers. In 2002, “Reggae Beat Goes On,” a reggae cover of “And the Beat Goes On,” was released by Family Choice. Then in 2019, “How Long?”, a song containing elements of “Reggae Beat Goes On,” was released by Vampire Weekend.

“Reggae Beat Goes On” is a cover of “And the Beat Goes On,” and uses a very original arrangement in order to shift the genre from disco to reggae. The melody and lyrics remain the same and the chord structure is nearly the same as well, but the rest of the musical setting is different. “How Long?” takes elements from the musical setting of “Reggae Beat Goes On” and interpolates them in the new song. Namely, the guitar part from “Reggae Beat Goes On” is played on bass guitar in “How Long?” There are string parts brought over to “How Long?” from “Reggae Beat Goes On,” and the chords in both songs match as well.

Who are the credited writers for “How Long?”? There are five: Ezra Koenig, member of Vampire Weekend; Ariel Rechtshaid, producer of the record; and William Shelby, Stephen Shockley, and Leon F. Sylvers III, all writers of “And the Beat Goes On.” Bill Campbell, arranger of “Reggae Beat Goes On,” receives no songwriting credit for “How Long?” despite having written the external elements that are present in “How Long?”, while Shelby, Shockley, and Silvers receive credit despite not having written the material that was borrowed.

The result here seems absurd—the people receiving credit (and thus, also receiving royalties) did not actually write the borrowed material. However, the result is somehow in line with the purposes of and justifications for US copyright law. US copyright law is explicitly founded upon a utilitarian theory. Under a utilitarian theory, lawmakers have to decide which types of works to prioritize for copyright protection. And in reading 17 USC § 115(a)(2), it is clear that Congress chose not to give priority to arrangements of songs prepared under mechanical licenses. If US copyright law was founded upon a natural rights theory and all new works were automatically granted protection, this problem would likely not exist, but that is not the case—Congress must weigh the costs and benefits of expanding protection. Here, the absurd results justify Congress intervening.

One way to remedy this problem is to revise 17 USC § 115(a)(2) to automatically extend protection to arrangements prepared under mechanical licenses, even if the copyright owner has not expressly granted consent for the arrangement to receive copyright protection. If drafted carefully, the consequences would be minimal—the law would have to delineate which elements of the new arrangement are not eligible for protection, and in order to do that, the arranger would only have to look back to see what elements of the original song are afforded protection. Those protected elements would then be excluded from the protection afforded to the arrangement, while the rest of the elements, as well as the arrangement as a whole, would receive copyright protection. A revised version of 17 USC § 115(a)(2) could read as follows

A compulsory license includes the privilege of making a musical arrangement of the work to the extent necessary to conform it to the style or manner of interpretation of the performance involved, but the arrangement shall not change the basic melody or fundamental character of the work. All elements of the arrangement that are not subject to copyright protection under the original copyright shall be subject to protection as a derivative work under this title.

Congress made an explicit choice to not automatically extend copyright protections to arrangements prepared under mechanical licenses. In order to prevent absurd results that end with authors receiving credit for material they did not write and thus, receiving royalties for this work that they did not create, it would be prudent of Congress to revise 17 USC § 115(a)(2) to automatically provide copyright protection to arrangements of musical works prepared under mechanical licenses.

Michael Pranger is a 2nd year JD student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

What’s The Issue?

It seems logical that the creator of a work would own the rights to that work. This general idea imports easily into some industries but creates problems in the music industry. The reality is that the main rights holder of a creative musical work is often not the musicians but collective management organizations (CMOs). After pouring countless hours, days, months, and years into perfecting a single music work or album, the musician often ends up not having total control over his or her work. The music industry is driven by smoke and mirrors where the distributors and records labels often do not disclose who owns the rights to which musical work. George Howard, co-founder of a digital music distributor called TuneCore and professor at Berklee College of Music, describes the music industry as one that lacks transparency. He explains that the music industry is built on asymmetry where the “under-educated, underrepresented, or under-experienced” musicians are deprived of their rights because they are often kept in the dark about their rights as creators.

As a result of the industry having only a few power players, profit is meek for musicians. Back in the day, musicians and their labels were able to get a somewhat steady source of income through physical album sales. However, with the prominence of online streaming, their main source of income has changed. The source of this issue seems to stem from how creators’ rights are tracked and managed.

A piece of music has two copyrights, one for the composition and one for the sound recording, and it is often difficult to keep track of both because the ownership of these rights are split amongst several songwriters and performers. The music industry does not have a way to keep track of these copyrights, and this is an issue especially when there are several individuals involved in creating a single musical work. With the development of digital ledger technology and its influence in various industries, it could be time that this development makes its way into the music industry and provide a solution to compensate musicians for their lost profits.

Blockchains: the solution?

Lately, blockchain technology has been at the forefront of conversations. For example, the variation in Bitcoin’s pricing has been a hot topic. Blockchain technology seems like a mouthful, but it is simply a “database maintained by a distributed network of computers.” Blockchains allow information to be recorded, distributed across decentralized ledgers, and stored in a network that is secure against outside tampering.

With the advancement of online music streaming, and entertainment going digital, blockchain seems like the perfect tool to be used in this industry. Since the issue of weakened profits seems to stem from disorganized tracking and monitoring of creators, blockchain technology could be utilized to improve the systems used for licensing and royalty payments. A blockchain ledger would allow a third party to track the process of a creative work and be an accessible way of managing intellectual property rights of these creative works. By tracking and monitoring their works, musicians could potentially gain back their profits, or at least recuperate some of their losses.

In 1998, there were several companies that came together to create a centralized database to organize copyrights for copyright owners so that royalty payments would be made in an orderly fashion. This effort was called the Secure Digital Music Initiative (SDMIT) and its purpose was to “create an open framework for sharing encrypting music by not only respecting copyrights, but also allowing the use of them in unprotected formats.” Unfortunately, this initiative failed to provide a universal standard for encrypting music.

The latest venture was the Global Repertoire Database (GRD) which aimed to “create a singular, compiled, and authoritative ledger of ownership and control of musical works around the world.” This was a very ambitious move and required two rounds of financing which consisted of the initial startup funds and the funds to cover the budgeting for the year. Although there were significant contributions to this mission, some collection societies, such as the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), started to pull out of the fund due to GRD’s failure and debt that it accumulated.

Even though this venture failed to provide a centralized database that could resolve royalty and licensing issues, there is now a growing consensus in the music industry for a global, digital database that properly, and efficiently, manages copyright ownership information. The next venture could utilize blockchain technology because of the advantages for storage, tracking, and security that it offers. In addition, not only could blockchain provide a centralized database so that music content information is accurately organized, it could provide a way to close the gap between creators and consumers and dispose of intermediaries. This would allow for a more seamless experience and transparency for the consumer and allow the creators to have more control over their works. Further, this ledger would allow these creators to upload all of their musical work elements, such as the composition, lyrics, cover art, video performances and licensing information, to a single, uniform database. This information would be available globally in an easily verified peer-to-peer system.

On the other hand, since blockchains are tamper-resistant, the data could not be “changed or deleted without affecting the entire system” even with a central authority. This means that if someone decides to delete a file from the system, such a deletion will disrupt the whole chain. There could also be issues with implementing such a large network of systems, or computers, due to the sheer amount of music that is globally available. Additionally, to identify each registered work, the right holders have to upload digital copies of their works which would require an extensive amount of storage and computational power to save entire songs.

Nevertheless, blockchain could provide the base for implementing a centralized database using a network of systems, or computers, in order to organize royalty payments for these musicians. Proponents contend that, with the help of Congress, this could be made possible. Congress recently introduced Bill HR 3350, Transparency in Music Licensing and Ownership Act. This act, if passed, will require musicians to register their songs in a federal database or else forfeit the ability to enforce their copyright, which would prevent them from collecting their royalties for those works. Although this might seem like an ultimatum, this proposed Act would provide the best way of changing how the music industry stores its information to provide an efficient way to distribute royalties and licensing payments to these artists.

Conclusion

People are split in their opinions about blockchain technology in the music industry. There are some who see this as a more accurate way of managing “consumer content ownership in the digital domain.” Others do not see this as a viable plan due to its lack of scalability to compensate for the vast amount of musical works. Even with the development of the music industry into the digital field, the goal is always to protect the artists’ works. Plan [B]lockchain ledger may not completely solve the royalty problem in the music industry, but it can provide a starting point in creating a more robust metadata database and, in combination with legislative change, the musical works could remain in the hands of their respectable owners.

Jenny Kim is a second-year law student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

Introduction

Throughout the past two years, AI-powered stem-splitting services have emerged online, allowing users to upload any audio file and access extracted, downloadable audio stems. A “stem” is an audio file that contains a mixture of a song’s similarly situated musical components. For example, if one records a mix of twenty harmonized vocal tracks, that recording constitutes a vocal stem. Stems’ primary purpose is to ease integrating or transferring their contents into either a larger project or a different work. Traditionally, only producers or engineers created and accessed stems. Even when stem sharing became commonplace, it was only for other industry insiders or those with licenses. But AI stem-splitting technology has transformed stem access. For the first time, anyone with internet access can obtain a stem through stem extraction software, which will likely push music production’s creative envelope into new realms. One inevitable consequence, however, is the question of copyright protection over stems extracted from copyrighted works.

Section 102 of Title 17 extends copyright protection not only over the stems’ original copyrighted audio source but also over that source’s components, such as the stems. Any modification of that work, such as extracting a stem and using it elsewhere, likely qualifies as a “derivative work” under Section 103. Importantly, Section 106 allows only copyright owners to authorize making derivative works. In light of this regime, what flexibility, if any, do artists have in using AI-extracted, copyrighted stems? Three considerations shed light on an answer: fair use, de minimis use, and the use of content recognition software coupled with licensing.

Fair Use

Codified under Section 107, the fair use defense provides a possible safeguard for would-be infringers. To establish this affirmative defense, a court would need to find the statute’s four factors sufficiently weigh toward “fair use.” Unfortunately, courts reach incongruous interpretations of what permissible fair use includes, rendering the defense a muddled construct for many artists. Squaring the four factors with stem usage, however, may offer guidance.

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit education purposes

In the seminal music fair use case, Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., the Supreme Court emphasized that this first factor will likely weigh toward fair use when the work is “transformative.” The Court went so far as to note “the more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors . . . .” Thus, an artist fearing infringement should strive toward transforming the copyrighted material into something distinct, used for noncommercial purposes. In the absence of a bright-line rule from the Court, however, artists will still need to use reasonable judgment about what types of stem usage is “distinct.” For example, suppose Artist A extracts a strings stem from a copyrighted work and only uses two seconds of it within another work that comprises numerous other instruments and melodies. Meanwhile, Artist B extracts the same strings stem; however, Artist B uses the entire strings melody within their work and only adds percussion and minor counter-melodies. Artist A would likely be in a more favorable legal position than Artist B given A’s efforts to materially transform the copyrighted audio.

The commercial nature of copyrighted stem usage is also unclear. An artist may choose to work with stems for solely experimental purposes. For example, an artist who shares their work via Soundcloud or YouTube does not expect another person to use those platforms to directly purchase the work. With stems’ increasing public accessibility, many will simply want to experiment with a music tool that, until recently, has largely remained a foreign concept. If this issue reaches a court, the court would need to conduct an analysis set against the landscape of such heightened accessibility. An increase in this noncommercial, creative use may offer hope to artists in the future, but it is too soon to tell.

- The nature of the copyrighted work

The second factor favors artists borrowing from copyrighted works with lower creative value. Unfortunately, music is typically found to be one of the most creative forms of copyrighted work. For example, a district court in UMG Recordings, Inc. v. MP3.Com, Inc. analyzing this second factor noted that the disputed material—copyrighted musical works—was “close[] to the core of intended copyright protection” and “far removed from the more factual or descriptive work more amenable to ‘fair use.’”

Though courts’ future inquiries into stem usage may differ from previous analyses of sample usage, the inquiry will likely change very little for this factor. Although a stem could potentially represent only a minute portion of the song, this factor’s inquiry focuses on the source of the stem, rather than the stem itself. Consequently, rarely will this factor work to a potentially infringing artist’s benefit, even if their stem usage is quite minor.

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole

The third factor, however, may offer hope for such minor stem usage. Courts will undoubtedly reach differing interpretations about how minimal the copyrighted portion’s “amount” and “substantiality” must be for this factor to weigh toward fair use. A court will need to weigh numerous variables and how they intersect. For example, is an artist using a thirty-second loop of a vocal stem or a five-second loop? Does that vocal stem include the chorus of a song? What about any distinct lyrics? Just minor humming? These considerations are not entirely novel. Artists purporting to use copyrighted samples have long been able to argue—with little success—that their samples’ amount and substance pass muster under this factor. Yet, stems are not samples; in fact, they typically represent a considerably smaller portion of a work. Given just how recent and novel their public accessibility is, it remains unclear whether a court would treat stem use any differently under this factor than it has treated instances of sample use. Carefully using a minor portion of a vestigial stem to avoid a work’s core substance, therefore, could potentially facilitate a favorable outcome.

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work

The fourth and final factor of fair use is “[u]ndoubtedly the single most important element.” This factor examines both the infringement’s effect on the potential market and “whether unrestricted and widespread conduct of the sort engaged in by the defendant . . . would result in a substantially adverse impact on the potential market for the original.”

In the sampling realm, this factor has tipped the scales before. For example, in Estate of Smith v. Cash Money Records, Inc., a district court found fair use when the defendants inserted a thirty-five-second “spoken-word criticism of non-jazz music” into a hip-hop track. In its analysis of this fourth factor, the court emphasized that “there [was] no evidence” that pointed to overlapping markets between the spoken jazz track and the hip-hop track. The court, noting this factor’s high probative value, then weighed this factor in the defendants’ favor.

In the stem realm, the novel nature of widespread public use means courts will need to determine both whether this factor should remain highly probative and how much deference to give stem users in analyzing market overlap. After all, an artist who incorporates a stem into a work intended for a twenty-five-person YouTube following likely affects the original work’s market differently than an artist who disseminates that work to millions of followers. This factor’s outcome will also rely on the stem’s source. Similar to sampling, if an artist uses a stem in a drastically different arena than the one for which the stem was created, this factor will weigh more toward fair use.

For example, suppose Artist A locates an insurance advertisement jingle. Artist A then extracts a stem from that advertisement audio and uses the stem in a new hip-hop track. The advertisement’s potential market is likely different from the hip-hop track’s potential market. Artist A’s work would likely have little impact, if any, on the advertisement’s market. Artist B, meanwhile, creates a hip-hop track but uses a stem from another hip-hop song produced twenty-five years ago. Though Artist B may believe the stem from the older hip-hop track no longer caters to the same hip-hop market to which Artist B is targeting, a court may be more inclined to find a material impact on the older track’s market: it would provide another way in which music listeners, particularly hip-hop listeners, could hear that older track. Nonetheless, it would remain up for a court to decide.

De Minimis Use

Artists might also be able to use extracted, copyrighted stems if such use is de minimis. The Ninth Circuit in Newton v. Diamond held de minimis use—“when the average audience would not recognize the appropriation”—is permissible. Yet, following the Newton decision, the Sixth Circuit in Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films foreclosed the possibility of de minimis copying. Similar to fair use analysis, it is difficult for an artist to determine whether the use of a stem in their work is de minimis under this standard.

Thus, an artist who loops only a small, relatively generic-sounding portion of a stem may find additional legal protection. But they might not. If they are in a jurisdiction that does not recognize de minimis use, or they use a stem in a way that extends beyond what a court considers de minimis in a de minimis jurisdiction, this avenue will be unavailable.

Content Recognition Software

Beyond legal defenses, a newer scheme of licensing deals coupled with content recognition software may offer protection for stem usage. For example, if a user on the content platform TikTok uploads content with copyrighted audio, TikTok’s content recognition software recognizes the audio, then pays the appropriate royalties to the audio’s copyright holder through preexisting licensing deals. Yet, because schemes like TikTok’s and stem usage are both relatively new, it remains unclear whether artists could find the same protection through individual stem use. Indeed, if an artist uses only a small part of a single stem, it may very well be impossible to detect the stem’s source; however, emerging technology may change this soon. Further, these licensing deals restrict such artists to sharing work only on particular platforms—notably, neither Soundcloud nor YouTube. Ultimately, this protection carries promising potential for expanded, authorized stem use. But perhaps not quite yet.

Matthew Danaher is a second-year law student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

What are Copyright Bots?

Digital media handles like Instagram, YouTube, and Tik Tok are now the platforms of choice for creators, new and old, to showcase their work. The accessibility of these platforms opens an untapped market of creativity, allowing for anyone with a smartphone to disseminate their work. With great freedom, though, the potential for copyright infringement skyrockets.

This is where copyright bots come in. Also known as content recognition software, copyright bots are automated systems programmed into digital media platforms that compare uploaded content against an archive of copyrighted content to recognize similar works. The copyright owners, or the platforms utilizing copyright bots, can then examine the similar works to determine whether the work is an actual copy, whether the copy is licensed, and whether legal action to remove the work is merited. Some bots can even handle the enforcement of the copyright by sending out notices and handling appeals.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) of 1998 is one explanation for the popular use of copyright bots. Under the Act, online service providers can be held liable for direct infringements of copyrighted work made by its users that they are aware of, regardless of whether they are responsible or receive any kind of financial benefit from the infringement. Fortunately, the safe harbors provision of the DMCA provides immunity from secondary infringement liability as long as the online provider swiftly removes and disables access to the infringing material. This incentivizes providers to use automated systems capable of acting expeditiously.

Another explanation for the use of copyright bots is necessity. There is simply too much new content being uploaded for humans to manually search on their own. To put it in perspective, 720,000 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every day. If human reviewers are equivalent to a guard dog, then copyright bots are an entire army, able to identify, analyze, and compare uploaded content at a rate that is not viable for humans.

The Benefits and Risks of Copyright Bots

Copyright bots provide substantial benefits to copyright owners and digital media platforms. Without bots, it would take a lifetime for copyright owners to police a fraction of YouTube’s content alone. Humans’ limitation in identifying similar works results in thousands, even millions, of works neglected under the radar.

Copyright bots, on the other hand, provide a copyright owner with an all-inclusive overview of similar works because they can effortlessly sift through content at a relatively instant speed. They can also enforce a copyright owners rights without any oversight. Consequently, this automated method identifies all matches, allowing copyright owners to comprehensively enforce their rights against all, instead of just a fraction, of unauthorized uses.

Digital media platforms also benefit significantly from the use of copyright bots. According to YouTube, over 98% of copyright issues on the platform are handled by their content recognition software. With the eminent risk of liability under the DMCA, it’s no wonder why YouTube and other platforms use overzealous copyright bots.

Nevertheless, copyright bots pose several risks. First, copyright bots are far from perfect and tend to produce false positives. The automated systems often flag content that uses a de minimis amount of copyrighted material, or material that is in the public domain. In particular, bots do not have an ear for classical music, which exists as a frequently revisited collection of public-domain works that are distinguishable through slight variations in performance.

Copyright bots’ tendency to produce false positives disproportionately favors the interests of digital media platforms and copyright owners. Both groups have an incentive to remove as many close matches as possible, even when they are false positives that don’t constitute infringement. This is especially true for digital media platforms that are motivated to rigorously comply with the DMCA’s notice-and-takedown process to shield themselves from liability. Overall, there is little to no deterrent for digital media platforms and copyright owners to eliminate any and all content identified by the bots.

On the other hand, the odds are against content creators when they appeal a takedown notice. If they lose on the appeal, they risk having their digital media accounts blocked and being forced to pay a high licensing fee or settlement payment. Content creators fear receiving a takedown notice every time they post new content. Doug Walker, a popular YouTube host, said that his fear of takedowns when administered by a bot has made him never feel safe posting a video, even though “the law states that [he] should be safe” posting his videos. As a result, many content creators, like Walker, choose to censor themselves instead of gambling on an appeal.

Second, copyright law is intended to allow for flexibility and discretion in the analysis of whether a new work infringes a protected work. Bots, however, are unable to decipher the difference between fair uses of a copyrighted work—works that are a parody, intended for educational purposes, or have been transformed—from works that are infringing.

For example, Richard Prince’s series of paintings called “Canal Zone,” in which Prince added an animated guitar and eyes to an existing photographic work of a Rastafarian man, likely would be signaled and shot down by copyright bots. But the court in Cariou v. Prince found that “all but five of Prince’s works do make fair use of Cariou’s copyrighted photographs.”

Bots’ limited ability to recognize the limitations on copyright law risks granting monopolies to the original owners, which is something copyright law is intended to prevent.

Copyright Bots’ Impact on the Policy Goals of Copyright Law

In addition to the short-term effect on content creators, copyright bots’ deficiencies ultimately harm copyright law’s policy goals. Copyright law stems from Article 1 Section 8 clause 8 of the Constitution: “Congress shall have power to… promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries…” Under the United States’ utilitarian perspective, the exclusive rights of reproduction, adaptation, publication, performance, and display afforded to copyright owners is intended to foster creativity and innovation to benefit the public. What copyright law does not grant, however, is a monopoly over original works with a modicum of creativity.

Copyright bots do a good job of protecting owners’ rights across a broader range, and they help keep digital media platforms within the safe harbors of the DMCA. However, overreliance on copyright bots risks granting monopolies to copyright owners and turns a blind eye to the intended limitations on copyright law. This is especially true when the bots themselves are also in charge of enforcement.

Moreover, the bots’ rigorous administration of owners’ rights fails to acknowledge the lawfulness of works that supersede the objects of original creation or add something new with further purpose or different character. Transforming a copyrighted work or using it for educational purposes benefits society and achieves copyright law’s policy goals.

If digital media platforms continue to take a back seat while bots drive enforcement, copyright law in the online world will discourage creativity and innovation. Ultimately, this will halt the advancement of science and the useful arts. Even worse, creators may start focusing on ways to avoid copyright bot detection instead of spending time adding value, information, or new aesthetics to copyrighted material, thereby failing to further progress and protect owners’ rights.

Moving Forward

Copyright law’s design leaves room for discretion to balance the tension between copyright owners’ rights and creators’ liberty. Digital media platforms should embrace the permitted use of copyrighted material to maintain the peace between copyright owners and creators instead of unleashing their bot armies on the slightest hint of a potential infringement. As human oversight dwindles, and the use of bots rises, creators will be forced to learn the bots’ algorithm to avoid attacks instead of enjoying and capitalizing on their freedom under the fair use doctrine.

The easiest solution would be to eliminate copyright bots entirely. However, bots are necessary considering the sheer volume of new content uploaded every minute. Nonetheless, they need revision to be more skeptical of works that are similar to or contain copied material. There also needs to be human oversight, especially during the enforcement stage, until copyright bots can differentiate between infringing works and fair uses. It’s time for copyright bots to receive a much-needed tune up before they rewire content creators and deprive the online world of their artistry.

On July 1, 2021, the original source code for the World Wide Web sold for $5.4 million at a Sotheby’s auction. This was not the actual source code, which is open source and freely available in the public domain, but rather a non-fungible token (NFT) version of the source code. NFTs, a new block chain based asset, have been making waves as everyone — from artists, sports leagues, to exiled whistleblowers and institutional investors — looks to participate in the craze by creating and selling digital assets for millions of dollars. (See also) So, what are NFTs, and what property rights and liabilities do buyers take on with their purchases?

What are Non-Fungible Tokens?

Non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, are unique digital assets stored on blockchain and used to create authenticated digital ownership of a scarce asset. The concept was first introduced by Vitalik Buterin, creator of the fungible crypto currency Ethereum, in December 2012 with “Colored Coins.”

An NFT uses “smart contracts,” which are open-sourced blockchain protocols outlining specific terms and conditions for the transfer of digital ownership. The smart contract is then permanently “minted,” or stored onto a blockchain token (most commonly Ethereum) creating an immutable record of the token’s history, from its creation all the way to its most recent sale. The secure digital storage of ownership records is one of the chief benefits of NFTs as a vehicle for storing wealth, especially compared with similar markets, like art, which are often plagued with authentication problems.

In 2017, the potential for digital assets as a means to store and create wealth was first initiated when CryptoPunks launched the world’s first marketplace for NFT digital art on the Ethereum blockchain. The project’s creators distributed 10,000 different claimable cartoon characters to entice market participants, and the characters were quickly claimed and subsequently traded in a freely formed secondary market.

State of the Market Today

Today, the NFT market is exploding. For example, on August 28, 2021, just four years after launch, CryptoPunks crossed $1 billion in all time sales. Much of this growth has occurred over the past twelve months. During 2020, NFT sales are estimated to have totaled a mere $94.7 million; however, for 2021 NFT sales have sky rocketed all the way to $24.9 billion. Much of this growth occurred in the second half of the year with sales volume growing from a combined $2.1 billion during Q1 and Q2 to a combined $22.3 billion during Q3 and Q4. Despite current volatile equity markets, NFTs continue to remain popular during 2022, with OpenSea, the largest NFT marketplace, announcing a record $5 Billion in transaction volume for the month of January.

Much of the NFT growth has been attributed to increased demand and acceptance for cryptocurrencies, coupled with an increased participation in public consumer trading during the COVID-19 pandemic. The explosive growth has drawn increased media attention, which has further fueled its virtuous cycle. Today, blue-chip companies like Coca-Cola are issuing their own NFTs, while institutional investors and fund advisors like Andressen Horowitz are investing heavily in the NFT marketplace, demonstrating confidence in its continued growth. Accordingly, this formerly fringe product has come under increased legal and regulatory scrutiny.

The scope of transferred property rights with NFTs

The rights acquired by an NFT purchaser vary widely based on how and where the NFT was acquired. In most cases an NFT holder, similar to a purchaser of a physical collectible, is purchasing a non-exclusive license to the underlying intellectual property rights of the asset for a non-commercial purpose. However, unlike a physical collectible, a digital NFT is easily and cheaply created, reproduced, or downloaded. A crucial distinction is that an NFT holder is merely acquiring the rights to the blockchain token imprinted with the intellectual property, and not the underlying intellectual property itself. Furthermore, for many NFTs the blockchain is unable to store the actual underlying digital asset, so what is actually being bought is an imprinted link to the asset. As a result, the underlying copyright only transfers if the copyright’s owner assents to such transfer in writing alongside the transfer of the digital asset.

The totality of the rights associated with the token are defined by the smart contract. Thus, there is a huge importance on the drafting of the smart contract coded into the token during an NFT transaction, which is an element not evinced during a physical collectible sale.

Smart contracts are the coded instructions of the NFT defining the scope and limitations of use. Depending on where the NFT is acquired the license agreement can vary immensely. The NBA Top Shot platform is an example of a proprietary marketplace, meaning the NFTs are created by a single market operator who does not allow third party transactions. For their platform, Top Shot has promulgated an internal standard NFT license agreement. These kinds of agreements stipulate that the buyer receives, “(i) a personal license to use and display the art associated with the NFT, as well as (ii) a commercial license to make merchandise that displays that art associated with the NFT, a license subject to a $100,000 gross revenue per year limit.” Given the market operator is minting all listed products, this concentrates even more control in the market operator and typically transfers the fewest rights to the subsequent owner, as evidenced by Top Shop limiting the ability of future owners to commercialize their purchase.

On the other end of the spectrum is OpenSea, an example of an “open” marketplace that allows anyone to mint and sell NFTs and enables customizable licenses. For example, an NFT of a tungsten cube sold for $200,000 and included the right to touch a physical one-ton tungsten cube stored at Midwest Tungsten Service headquarters once per year. This market offers financial freedom, but also features high risk of fraud due to ease of access, lack of market oversight, and difficulty in tracing actual wallet ownership.

In the middle are curated marketplaces, which require artists to apply to have their items listed by the market operator; however, unlike proprietary marketplaces, any creator can apply to have their NFT listed so long as the NFT conforms with the market operator’s regulations. Approval generally requires the NFT seller to abide by the market’s standard license agreement, similar to the proprietary market.

Regardless of who is dictating the terms, NFT license agreements cover a variety of issues tied to which property rights are being transferred. Typically, this includes many common terms and conditions such as indemnification clauses, buyer and seller rights, and definitions for various duties and obligations amongst others. However, the intrinsic qualities of an NFT also necessitate some atypical clauses such as ownership of platform IP, digital wallet verification, and outlining the commercialization or transfer rights. The most important and heavily scrutinized term of an agreement though is how the agreement handles the ownership of the copyright connected to the token. Thus, understanding the terms contained in these agreements is essential to evaluating and participating in this fast growing and evolving digital marketplace.

The potential for copyright infringement and liability for NFTs

While blockchain can authenticate the transactions, blockchain is unable to inform the buyer if the seller has rights to underlying copyrighted work or is merely selling someone else’s copyrighted work. This is important because section 504 of the Copyright Act holds even an innocent actor who unknowingly violated somebody else’s copyright automatically liable for both actual and statutory infringement damages. Recently, an NFT of Whales produced by a 12 year old programmer was sold for thousands of dollars, only for the images to later be discovered to have been copied directly from another project. Assuming the use constituted infringement (the issue has not yet been litigated), the buyer at a minimum is liable to return the NFT to its rightful owner and handover any profits. Furthermore, if the buyer knew there was a potential infringement and still sold the NFT, the statutory liability could be over a million dollars.

Conclusion

NFT case law is still being developed, with the first cases just now working their way through the legal system. As the market continues to grow, more regulatory agencies, including the SEC, are taking a closer look at security status and potential acts of fraud. However, until the regulatory status is cleared NFTs exist in a caveat emptor market. The onus is on the purchaser to verify the terms of the license agreement they are acquiring, the status of the seller, and the underlying intellectual property. While blockchain makes the verification and authentication process easier, it still has gaps creating additional liability, especially for copyright infringement.

TRIPS Waiver and COVID-19 Policy

As COVID continues to impact nations across the world, policymakers are left trying to facilitate ways to better deal with a global event of this magnitude. Public health concerns forced leaders to re-think current laws and agreements. Intellectual property law is not an outlier. To mitigate some of the effects of the pandemic, some countries have tried to waive certain intellectual property rights for knowledge sharing. In October of 2020, for instance, India and South Africa proposed a TRIPS waiver related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which sparked a global debate around balancing intellectual property rights and managing a global health crisis.

Countries that are members of the WTO have all signed agreements related to trade and intellectual property protection–this agreement is the TRIPS agreement. Governments that have agreed to this TRIPS agreement can bring waivers, such as the one proposed now, in times when they believe the public good may be better served without certain IP protections. The idea is that waiving certain obligations pertaining to either patents related to COVID-19 related inventions or discoveries would allow greater access to COVID-19 vaccines and drugs. India and South Africa’s proposal was amended in May of 2021, with the support of 60 low-income countries. The main amendment was the addition of a clause that limited the waiver to cover a period of three years. The waiver would cover “health products and technologies, including diagnostics, therapeutics, vaccines, medical devices, personal protective equipment, their materials or components, and their methods and means of manufacture for the prevention, treatment, or containment of COVID-19.”

Support for this waiver has expanded to more countries, including China, but notably it did not receive initial backing from the U.S. The U.S. has historically been opposed to such intellectual property waivers. However, on May 5, 2021, the Biden Administration released a statement in support for a TRIPS waiver for COVID-19 vaccines, specifically. It stated, “The Administration believes strongly in intellectual property protections, but in service of ending this pandemic, supports the waiver of those protections for COVID-19 vaccines.”

More than a year after India and South Africa’s initial TRIPS proposal, discussions continue among WTO nations, but no agreement has been reached. Countries like Germany, Switzerland, Norway, and the UK are standing firm in their objections. Though as of January 2022, roughly 10 billion doses of the COVID-19 vaccine have been administered, Our World in Data reports that only 10% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose.

Would Climate Change Fit Under a TRIPS Waiver?

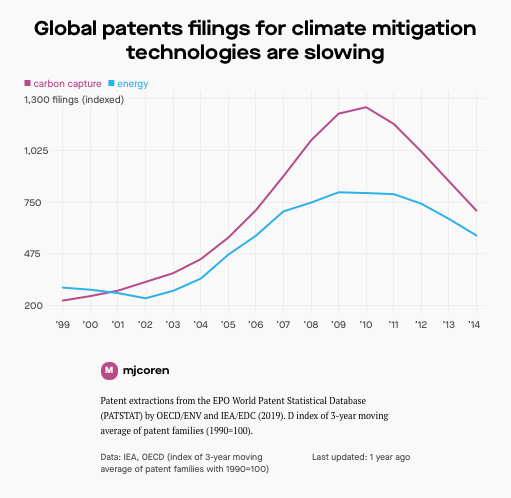

If a TRIPS waiver cannot be approved for something as global and life-threatening as the COVID-19 pandemic, can a TRIPS waiver ever be approved for something else? In the face of impending climate change, for example, could a TRIPS waiver be effective in the sharing and access of climate technologies, much as a COVID-19 waiver would be effective in sharing technologies related to the pandemic?

Simply put, yes. Climate change could be similarly categorized as a type of disaster that could be noted in a TRIPS waiver proposal to temporarily waive intellectual property rights, specifically patent protections. However, at this point, a TRIPS waiver for climate change has not been formally proposed.

Possibility of Extended TRIPS Waiver to Combat Climate Change

Just as with the COVID-19 pandemic, low-income countries are likely to suffer the most from climate change. Like with COVID-19 relief, knowledge sharing of climate change technologies may be needed and desired. A TRIPS waiver could promote “technology transfer” related to climate change, which in turn could promote access to climate technologies, especially in low-income countries. This sharing of knowledge would ideally lead to developments in climate technology and further access around the world.

However, opponents to TRIPS waivers state that without intellectual property protections, inventors are not sufficiently incentivized to continue to create new technologies. It is argued that stripping away financial incentives would hinder the development of climate technology and that the TRIPS agreement is in place primarily to guard those property rights of patent, copyright, and trademark owners. To secure a TRIPS waiver for climate change technologies, approval would be needed from many different countries. Low-income countries would potentially be more willing to sign on to this type of waiver, as evidenced by their support of the COVID-19 waiver. As has been the case with other proposed waivers, it will potentially be difficult to influence higher-income countries like the United States. Yet, since the Biden administration has supported a limited, temporary COVID-19 waiver, perhaps this administration or future administrations would support similar proposals relating to climate change.

Other high-income countries would need to sign on for the waiver to be effective and lead to knowledge sharing. As James Bacchus emphasizes in his report for a WTO climate waiver, being able to secure such a waiver will fall on the political persuasion of countries who hold the most power. It will take the persuasion of these countries in convincing the WTO that this type of waiver is necessary to battle the potential destruction of climate change. Drafting a climate change waiver and waiving certain intellectual property rights temporarily to create knowledge sharing of climate technologies would be the easy part of this venture. Getting the necessary support from countries who have the most power would be much harder.

Alternate Routes of Knowledge Sharing

A TRIPS waiver could allow access to intellectual property, specifically patents, within a timeframe normally unachievable under the current intellectual property regime. But is there another way to increase knowledge sharing, without relying on a TRIPS waiver being passed?

One alternative may be patent pools. The creation of patent pools has improved access to public health when intellectual property laws may have previously limited knowledge sharing. Patent pools are agreements between patent owners and/or third parties, to license a patent for others to use, create, or make. They work by allowing patent holders to license their patents to a shared pool. Then, manufacturers, developers, and other inventors that are part of this pool can use the rights to make the patented invention at lower costs. The patent holder gets royalties from what is sold, therefore allowing them to still benefit from their work. The Medicines Patent Pool, for example, operates to increase access to HIV treatments. It continues to create lower-cost drugs for those living with HIV/AIDS.

Applying the same idea, a patent pool could be created for climate change related technologies. The benefit of a patent pool is that it would not need broad approval from countries in the WTO, like a TRIPS waiver would need. A patent pool for climate change technologies would instead rely on the licensing of technology from patent holders themselves. Once the patent pool has patents that can be used, manufacturers can start to make and sell these inventions at lower costs, which would hopefully provide more access. The downside to a patent pool solution is that, though licensing patent holders would collect royalties, to make the pool work, all participants would need to agree on the licensing details. This would require that patent holders independently make the decision to share knowledge on their own and then agree with the other patent holders in the group. Without buy in from governments, the patent pool system relies on the goodwill and good faith of individual patent owners.

Conclusion

Ultimately, it would likely be difficult to set in place a TRIPS waiver for climate change technologies, even though such a waiver can be highly effective in promoting knowledge sharing. As a TRIPS waiver has not yet been available for COVID-19 related relief, trying to obtain buy in for a potential crisis that may be slower-paced than COVID-19, like climate change, would be challenging. However, without waiting for sign on from every country, effective knowledge sharing can still take place by adopting alternative plans like patent pools. Because patent owners would still receive royalties and be able to opt-in on their own accord, patent pools may be a particularly effective way to promote the sharing of climate change technologies.

Madeline Thompson is a second year law student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

Gambling, in one way or another, has been part of American life for centuries—early colonists participated in activities such as lotteries, betting on cock fights, and other games of chance. Throughout our history, gambling has remained a source of moral debate. On one hand, it is argued that Americans should be free to use their money how they see fit, and gambling typically consists of ‘harmless’ games. On the other, gambling can become a crippling addiction that leads many to economic hardship and is often tied to corruption and crime. This tension has resulted in a complex regulatory relationship between the government and the gambling industry. Nevertheless, gambling has only grown in popularity over the years and is now a massive industry that generated over 40 billion dollars in revenue in 2019 alone. The United States is now facing even more regulatory complexity as the rise of the internet and cryptocurrencies has rendered the existing regulations largely ineffective.

Throughout American history, regulating gambling has largely been the responsibility of each state. The federal government has taken a back seat role and typically gets involved only to supplement and support state law in the face of interstate gambling.

As with many aspects of modern life, the rise of the internet has quickly and drastically changed the gambling landscape. Online gambling sites began cropping up in the 90s, and people who lived in states where gambling was illegal were suddenly able to sign up online and make bets from anywhere. Even people in states where gambling was legal took advantage of the convenience of online gambling.

Many of these gambling sites were hosted abroad, resulting in the shift of a large portion of potential gambling revenue to offshore operations. Further, these online gambling hubs lacked any regulation and were much more likely to rig odds in their own favor or participate in money laundering schemes.

Finally, in 2006, the federal government deemed it necessary to take a more active role in regulating online gambling and passed The Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (UIGEA). The UIGEA did not go so far as to outlaw online gambling. In fact, it didn’t impose any liability on individual online gamblers and included a clarification in its purpose section that emphasized that the Act should not be construed as “altering, limiting, or extending any Federal or State law . . . prohibiting, permitting, or regulating gambling within the United States.” Instead, the Act prohibited businesses from accepting payments from people engaging in any form of illegal online gambling. The main provision reads: “No person engaged in the business of betting or wagering may knowingly accept [any form of payment], in connection with the participation of another person in unlawful Internet gambling.”

In effect, the Act put online gambling purveyors that accept payments from players in the United States in violation of the law unless they are directly authorized by a state and acting in accordance with that state’s laws and all bets or wagers are initiated and received within that singular state. It also prohibited financial institutions from processing any gambling payments.

Naturally, many online gambling sites stopped allowing players in the United States from gambling on their websites to comply with the law. But of course, some online gambling sites remained in operation. Online poker sites, for example, hoped that the vague language of the UIGEA did not cover poker, since poker can be characterized as a game of skill rather than of chance.

In 2011, though, the Department of Justice exercised its first major enforcement of the UIGEA and shut down these online poker sites, while at the same time freezing millions of players’ accounts, many of which held enormous sums of money. Mass chaos ensued. Avid online poker players refer to the date of the shut down as “Black Friday,” and as a result, ‘illegal’ online gambling largely tapered off for several years.

Currently, online gambling is legal in six states: New Jersey, Connecticut, Delaware, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Gamblers in these states can access and legally gamble on a small selection of state-authorized casino websites. These states have seen massive benefits from the legalization of online gambling. New Jersey, for instance, has generated over $600 million dollars in tax revenue since it first authorized online casinos in 2013.

However, those located in the remaining 44 states where online gambling is illegal were largely out of luck. Recently though, thanks to the rise of individual VPN use and cryptocurrencies, online gambling has had a huge resurgence. But of course, with this resurgence comes new legal implications and gray areas.

VPNs

A Virtual Private Network (VPN) is a service that allows you to encrypt your data and mask your computer’s IP address when you surf the web. It does so by connecting you to the internet via a secured private server, rather than through your own internet service provider. When using the internet through a VPN, websites you visit do not know your IP address, which normally connects your location and identity to your online activity. Instead, sites only know the IP address of the VPN. VPNs themselves are legal and a valuable way to use the internet while also protecting your personal data. But they also give people the freedom to do things they wouldn’t, or couldn’t, do if their activity were tied to their personal IP address.

American online gamblers have taken to using VPNs located in more gambling friendly countries in order to circumvent online casinos’ bans on American users. However, most of these sites ultimately require users to provide personal information in order to validate users’ identities prior to allowing them to deposit and withdraw funds. This validation step effectively filters out most American online gambling attempts. That is, until the rise of cryptocurrencies.

Cryptocurrencies