Author: Varun Bhatnagar

Introduction

In April 2022, someone paid $130,000 for a pair of Nike Dunks. Here’s the kicker – it was for a pair of virtual sneakers. Shelling out five to six figures for a pair of exclusive shoes is not rare in the sneaker world, but paying that much for a pair of virtual kicks is unprecedented.

This sale illustrates Nike’s wider strategy in conquering the next frontier of commerce: the metaverse. In 2021, Nike started making strategic investments to grow and protect its brand in the metaverse. First, Nike submitted several trademark applications with the United States Patent and Trademark Office for virtual goods. Second, Nike announced a partnership with Roblox, an online gaming platform, to create a Nike-branded virtual world where gamers can play virtual games and dress their avatar in digital versions of Nike’s products. Third, Nike acquired RTFKT, an organization that creates unique digital sneakers. John Donahoe, Nike’s President and CEO, described the acquisition as “another step that accelerates Nike’s digital transformation and allows us to serve athletes and creators at the intersection of sport, creativity, gaming and culture.”

Nike is not the only brand exploring the metaverse. Other brands are now offering virtual merchandise through NFTs, including other sportswear brands like Asics and Adidas, luxury fashion brands like Hermès and Gucci, and even fast-food chains like Wendy’s and Taco Bell. Despite these companies’ growing activity in the space, the application of current intellectual property protection to branded NFTs is still unclear. A recent complaint filed by Nike against StockX, a popular sneaker resale platform, illustrates this uncertainty. The outcome of this case could determine the scope of trademark protection in the metaverse and will have serious implications on the commercial viability of brands’ significant investments in the space.

The Nike StockX Lawsuit

In February 2022, Nike sued StockX, a popular sneaker resale platform, after StockX began selling Nike-branded NFTs alongside physical Nike sneakers. The complaint, filed in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, laid out several causes of action, including trademark infringement. Nike stated that it “did not approve of or authorize StockX’s Nike-branded Vault NFTs. . . Those unsanctioned products are likely to confuse consumers, create a false association between those products and Nike, and dilute Nike’s famous trademarks.”

In its answer, StockX raises two key defenses. First, it claims that its “use of images of Nike sneakers and descriptions of re-sale Nike products in connection with StockX NFTs is nominative fair use. It is no different than major e-commerce retailers and marketplaces who use images and descriptions of products to sell physical sneakers and other goods, which consumers see (and are not confused by) every single day.” Second, StockX raises a first sale defense, arguing that “Nike’s claims are barred, in whole or in part, by the first sale doctrine permitting purchasers of lawfully trademarked goods to display, offer, and sell those good under their original trademark.” Thus, the outcome of the case turns on how courts will apply traditional intellectual property doctrines to more modern trademark issues.

StockX’s Nominative Fair Use Defense

Nominative fair use is an affirmative defense for defendants who use another’s trademark deliberately to refer to that party, for purposes such as advertising, commentary, and news reporting. To raise a successful nominative fair use defense, the user must meet three requirements: “First, the product or service in question must be one not readily identifiable without use of the trademark; second, only so much of the mark or marks may be used as is reasonably necessary to identify the product or service; and third, the user must do nothing that would, in conjunction with the mark, suggest sponsorship or endorsement by the trademark holder.”

StockX can likely meet the first and second requirements but will struggle to meet the third. StockX can argue that it would be difficult to sell the virtual NFT Nike sneaker without using Nike’s trademarked logo and that it is only using the Nike logo as much as reasonably necessary for the consumer to identify the product. As StockX’s argues in its answer, “the image and product name on the Vault NFT play a critical role in describing what goods are actually being bought and sold.” As some have pointed out, the Nike logo “does not appear to be used by StockX separate and apart from its appearance in the photo of the shoes corresponding to the NFT.”

At issue is the third requirement regarding an implied sponsorship or endorsement. StockX’s website includes a disclaimer of any affiliation with the Nike brand, but it is unclear if this adequately safeguards against consumer protection. Nike’s complaint characterizes the disclaimer as “comically and intentionally small” and “difficult to read.” As evidence that the disclaimer does not prevent consumer confusion, Nike points to numerous social media users who expressed uncertainty as to whether Nike endorses, approves, or gets a commission from StockX’s NFT sales. This confusion is further compounded by the fact that Nike sells its own NFTs. Thus, StockX will likely have difficulty in succeeding on its nominative fair use defense.

StockX’s First Sale Defense

The success of StockX’s first sale defense requires a more complex, fact-intensive analysis. The first sale defense establishes that “the right of a producer to control distribution of its trademarked product does not extend beyond the first sale of the product.” Whether or not this rule applies to Nike’s case, however, depends on how the court characterizes the NFT. On one hand, StockX will argue that its NFTs are each tied to the resale of a physical Nike shoe – similar to a receipt – and thus fall under the first sale doctrine. On the other hand, Nike will argue that the NFTs are standalone, separate products and thus are not protected by the first sale doctrine. To succeed on the trademark infringement claim, Nike must establish that the NFT and the physical shoe are two independent products.

On its website, StockX added a disclaimer in an attempt to address this issue directly, “Please note: the purpose of Vault NFT is solely to track the ownership and transactions in connection with the associated product. Vault NFTs do not have any intrinsic value beyond that of the underlying associated product” (emphasis added). However, this disclaimer does not preclude Nike from demonstrating that there is a separate value and that the shoe and the NFT are independent products.

First, Nike can point to the fact that the NFTs being sold on StockX are generally more expensive than the value of the sneaker itself (even if one accounts for the markup of sneakers that is common in the resale market). Nike points to this divergence in monetary value: “Thus far, StockX has sold Nike-branded Vault NFTs at prices many multiples above the price of the physical Nike shoe.” For example, as of October 25, 2022, the Nike Dunk Low Off-White Lot 50 was on sale for $715. The NFT of that very same shoe, however, was on sale for $8,500. This significant divergence in price suggests that there is an independent economic value of the NFT beyond the ownership of the physical shoe.

Second, Nike can argue that the NFTs are an independent product because NFT ownership gives consumers unique perks. When the program initially launched, StockX’s website explicitly stated that NFT “owners may also receive exclusive access to StockX releases, promotions, events, as a result of ownership.” Since the lawsuit, this language has been removed, likely because it could be used as ammunition by Nike to defeat the first sale defense. But NFT owners still get some exclusive perks. For example, the ownership of the NFT means that StockX will store the physical shoe in their “brand new, climate-controlled, high-security vault” and NFT owners will be able to flip/trade the shoe instantaneously, rather than waiting for the shoes to be shipped or paying shipping fees. The storage and the ability to bypass shipping costs associated with flipping sneakers are benefits that are unique to owners of the NFTs but are unavailable to those who only own the physical show.

Conclusion

The Nike-StockX litigation highlights the uncertainty of how traditional intellectual property law applies to more modern trademark issues. The outcome of the case will have serious implications for how companies can protect their brands in the growing world of virtual commerce.

Jeanne Boyd is a second-year JD student at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

In August 2022, over two and a half years after the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, Moderna sued Pfizer and BioNTech for patent infringement. Specifically, Moderna claimed that Pfizer and BioNTech used its patented mRNA technology to develop their Covid-19 vaccine. Covid’s swift, widespread, and devastating effects and the urgent need for a vaccine accelerated a typically years-long research and development process into one short year. Although public health and humanitarian aid were undoubtedly at the forefront of vaccine developers’ minds, intellectual property (IP) rights and their economic incentives were a significant factor as well.

In the United States, IP laws regarding patent protection are largely based on utilitarian and economic theories. The monopolistic rights given to patentholders and the typical damages for patent infringement reflect these theoretical foundations. In its complaint, Moderna seeks “fair compensation” for Pfizer’s use of the mRNA technology, essentially a cut of Pfizer’s profits, which could potentially amount to billions of dollars from a period of only two to three years. Despite the billion-dollar vaccine industry, the strong economic bases of patent protection are potentially at odds with promoting scientific innovation. The critical need for worldwide Covid vaccines to save potentially millions of lives underscored whether utilitarianism and economics are always the best rationales for IP. Public policy considerations, including public health and humanitarian aid, may justify at least partial waiver of IP rights in certain circumstances. Even Moderna acknowledged this, professing in its complaint its “belief that intellectual property should never be a barrier” to the vaccine. The company initially pledged not to assert its Covid-19 patent rights against fellow Covid vaccine developers to reduce barriers to global vaccine access. However, billions of dollars in competitors’ profits and an amended pledge later, the biotech industry is now watching an imminent IP battle between pharmaceutical giants. This current situation is unique in many respects, due to not only the scientific, economic, and social significance of the patents at stake, but also the companies’ global reputations as leading medical innovators.

Moderna’s complaint alleges that Pfizer and BioNTech infringed Moderna’s patents on mRNA technology used between 2011 and 2016 in other vaccines. In the company’s press release, Moderna’s CEO also emphasized its prominence in the field of RNA technology and the substantial time and resources used to develop the technology that Pfizer copied. The infringement focuses on the chemical modifications Moderna introduced to mRNA to improve immune system evasion and the lipid nanoparticle formulation used to deliver the modified mRNA.

Like most patent infringement plaintiffs, Moderna has financial stakes as a top priority. Moderna ultimately seeks a portion of Pfizer’s profits from its Covid vaccine, citing Pfizer’s unjust “substantial financial windfall” from its allegedly unauthorized use of Moderna’s technology. Pfizer’s 2021 revenue from its Covid vaccine totaled over $36 billion, and it expects another $32 billion in 2022. Moderna also seeks enhanced treble damages, suggesting willful or bad faith infringement from Pfizer. These are bold claims coming from Moderna, a relatively young company founded in 2010, against the nearly two-century-old industry giant, Pfizer.

This lawsuit demonstrates the utilitarian and economic theories of IP law, particularly patent law, in the United States. Under these theories, patent protection incentivizes invention and innovation by giving the inventor a temporary but strong monopoly on their invention. This monopoly allows the inventor to exclude others from using their information and knowledge without authorization. Information is non-rivalrous and non-excludible and would otherwise fall victim to public goods problems. For example, free riders can wait for someone else to create the invention, and then replicate the invention at a much lower cost. The original inventor would thus be disincentivized to disclose their invention for fear of losing valuable profits in a market saturated with copycats. Patent rights prevent these detriments of information as a public good by giving the inventor legal control over dissemination of the information. Applying this theory here, Moderna would argue that its previous patents represented a tradeoff that the company would publicly disclose its valuable information on mRNA technology. In return, Moderna would receive a legally protected right to exclude others, including Pfizer, from using the information.

These economic theories are based on patent rights’ essential function to tightly control information use; however, free dissemination of information is critical for scientific research, including vaccine development. The utilitarian foundations of U.S. IP law may not align with vaccine research goals, particularly in urgent pandemic circumstances. In these time-sensitive situations, allowing simultaneous inventors access to each other’s research developments may best serve the public interest. Some critics even argue that patents and economic incentives are entirely unneeded for vaccine research and development. The highly specialized technical know-how required and the complex regulatory framework for entering the vaccine market naturally weed out copycat competitors and create a monopoly position without patent rights. Further, vaccine manufacturers are in a favorable position selling a product whose demand reliably far outstrips supply.

Despite this view, patent rights will likely still play a role in pandemic vaccine development. However, this role may be more detrimental than beneficial to inventors and ultimately consumers. Although an inventor would prefer to keep a tightly guarded monopoly on their lucrative vaccine technology, this economically driven IP strategy may exacerbate the pandemic. Research responses to pandemics may require inventors to relinquish potential profits from strong information monopolies in exchange for rapid information sharing to encourage life-saving follow-on innovation. Enforcing pandemic research patent rights can significantly limit advancements in vaccine development, the opposite of the intended goal to serve public health.

Moderna recognized this dilemma and in October of 2020, it initially pledged to not enforce its IP rights related to Covid-19 vaccines during the pandemic. Considering the myriad economic benefits of IP rights, this pledge may have seemed financially counterproductive for Moderna. However, it demonstrated that Moderna also knew of the unprecedented public health and policy concerns at stake and did not want to deter other researchers from simultaneously developing Covid vaccines. However, in March 2022, Moderna updated its IP pledge, instead committing to never enforcing its Covid-19 patents against 92 middle- and low-income countries, thus making this lawsuit possible. It remains a question whether the original October 2020 pledge caused any parties to reasonably rely on Moderna’s assurance and whether there may be legal contract obligations to Pfizer or other vaccine developers. Regardless of potential contract law disputes, the urgent pandemic needs for Covid vaccines drove Moderna to its “Global Commitment to Intellectual Property Never Being a Barrier to COVID-19 Vaccine Access” cited in its complaint. Money and economic benefits are a significant motivating factor in the lawsuit, but the public health and humanitarian considerations underly the policy concerns of the claim.

The Covid pandemic forced the IP field, the scientific community, and the global public health sector to reconsider the role of economic and utilitarian theories in patent rights. Although innovators deserve financial rewards for being the first to develop and license their vaccines, the intended widespread benefit of this biotechnology can be significantly limited with overly restrictive information monopolies. Due to the scope and effects of Covid, vaccines have taken a new meaning, representing the potential return to the pre-pandemic “normal” and restoring society and the economy. Thus, the patent rights for Covid vaccines might have more than just economic value; they also bring reputational influence of goodwill and societal stabilization. Other areas of IP, such as copyright and trademark law, are less rooted in utilitarianism and are partly based on the personhood theory, which relates the IP to the creator’s sense of self and identity. Patent law is less concerned with traditional expressive elements of creation. However, the humanitarian nature of Covid vaccine development and distribution may implicate some personhood concerns of distributive justice and fairness. During such global health crises, reducing some of IP’s economic barriers to information and focusing on the personal effects on vaccine distribution may better serve the public interest.

Overall, IP scholars and policymakers should consider how non-economic theories may be, at times, better suited for IP protection and can help shape a more dynamic patent law system. While patent law should still strive to incentivize innovation and creation, policies must also acknowledge the effects of purely economic motivations on patient health and global health disparities. The Moderna v. Pfizer lawsuit illustrates the mismatches between economic foundations of patent law, biotechnological and pharmaceutical innovation, and emergency or pandemic situations.

Shelby Yuan is a second-year JD-PhD student at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

Within the past decade, companies outside of the traditional financial services firms have disrupted the financial industry due to technology shifts. Gaming companies now offer in-game currencies creating virtual economies and technology companies like Venmo and Zelle have disrupted the digital wallet space. With the creation of new virtual economies comes additional risk for consumers. These market entrants create new venues for cybercriminal activity, such as scams and money laundering.

Video Games and Microtransactions

In-game currency in video games pre-dates the current trend of digital currency. Many video games give users the ability to expand their experience by creating a virtual economy. Players engage in microtransactions where real currency is exchanged for virtual currency to use within a video game. The video game industry generated $21.1 billion in revenue in 2020 and has risen in recent years due to the pandemic which led to a rise in people seeking entertainment through online gaming.

Many game companies incorporate in-game currency to extend a player’s game time. For example, Minecraft, a sandbox video game with over 238 million copies sold, developed its own currency called “coins” as well as a marketplace within the game. Other games with active in-game economies include Second Life and World of Warcraft. While the intention of marketplaces in video games is to give gamers new and exciting features that drive them to increase their play time, cyber criminals have tapped these platforms to engage in money laundering and fraud. These games have players from all over the world, generating risks of cross-border money laundering and financing terrorism.

There are several ways a cybercriminal can engage in money laundering. The first is through using Skins. “Skins” are customized looks or accessories that gamers buy in-app to enhance their characters and extend their play time. These items are purchased, traded, or earned within the game. Another way is through third-party skin gambling sites such as CSGOEmpire, or Thunderpick where people can bid on these add-ons in exchange for cash. People use multiple accounts to build their reputation, and then sell items to other members in exchange for cash, with the option to withdraw those funds. Another way that money laundering can occur is when criminals use game platforms to clean dirty money. They load their account with the dirty money using stolen credit cards or other means, then transact with others several times until the money is clean and withdraw those new funds. Lastly, cybercriminals leverage stolen credit cards to engage in money laundering. They build profiles in digital gaming economies with lots of in-game features, such as skins or in-game currency. Cybercriminals will then sell these accounts on the secondary market to another user in exchange for cash.

Money Laundering in E-Payments

With Covid-19, we also saw an increase in fraud through use of money transfer apps. Criminals find individuals to deposit funds into an electronic payment app and then move funds to various accounts in order to clean the money. The Secret Service has over 700 pending investigations regarding payment fraud specifically related to COVID-19 relief funds. While these apps are easy to use and provide flexibility to customers and businesses, oftentimes at no cost, they also have led to an increase in fraud as well as a lack of consumer protection. While the transactions may be small at the individual level, used often to pay someone back for a meal or another shared expense, in aggregate these digital payment apps see huge traffic. Customers transferred $490 billion through Zelle and $230 billion was through Venmo in 2021. The rise in popularity of digital payment channels have led to more avenues for fraudulent activity.

There are various types of scams that cybercriminals can engage in using digital payment services. Users can be targeted for phishing scams via text message. They also can be targeted for a reverse charge: a stolen credit card is used for the transaction, the goods are delivered, and then a few days later the charge reverses because the card is illegitimate, but the goods are already out of the seller’s hands. Additionally, the goods themselves may not exist: a buyer might transact on Zelle or Venmo with the intention of purchasing the product, authorize a payment, but never receive the item.

With the rise in digital payment services as well as fraud, there is a question about whether consumers should bear responsibility for their actions or if they deserve protection from the platform. Zelle was created in 2017 by banks to promote digital transactions. However, these same banks claim that they are not liable to protect consumers against fraud because they authorize each transaction. Additionally digital payment platforms are starting to participate in cryptocurrency, another area in which legislators are looking to regulate to reduce fraud and protect the economy.

Relevant Regulations and Challenges

There are various regulations that impact the use of digital currency services as well as video games in relation to money laundering and fraud; however, they may not be comprehensive enough to apply to these new platforms.

Title 18 §1960 of the U.S. Code criminalizes unlicensed operation of money transmitting businesses. This regulation was developed by Congress in response to money launderers’ shift towards nonbank financial institutions in the 1990s. While digital payment services would qualify as engaging in “money transmitting,” it is unclear if video games, and their in-game currencies would fall under the code’s definitions of “funds.” In-game currencies could be considered funds due to the existence of vast secondary markets. Accounts are often sold between users, and skins are auctioned on dedicated platforms. On the other hand, courts have found that in-game currency and virtual items do not hold real-world value and fail to meet the meaning of “money” (see Soto v. Sky Union, LLC, a class action lawsuit where the court held that in-game currency did not hold real-world value because they could not be cashed out into real currency).

Additionally, the European Global Data Protection Regulation (”GDPR”) challenges safeguards against money laundering through video games and digital payment services through individuals‘ “right to be forgotten,” which can impede traceability of money laundering and fraud identification.

The US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (“CFPB”) also has established regulations for unauthorized transfers. Under 12 CFR §1005.2, the Code of Federal Regulations defines unauthorized transfers as ones which are “initiated by a person other than the consumer without actual authority to initiate the transfer and from which the consumer receives no benefit,” but does not include a transaction by someone who was given access to the device to make the transaction. Additionally, the liability is capped at $50 or $500 depending on if they provide notice to the financial institution.

The federal government, under the USA PATRIOT Act, also regulates money transfer services. The intention of the Act is to lay groundwork to deter and punish terrorist attacks through law enforcement and money laundering protection. Venmo, which qualifies as a money transfer services, had to implement a Customer Identification Program and collect additional information (e.g. Social Security Number) to verify the identities of users making transactions in accordance with the Act. While the Act intends to crackdown to reduce money laundering criminals are now instead looking for other venues to transact. Video games serve as an alternative as they are full of users engaging in micro transactions, thereby making it easier for money launderers to blend in and harder for government agents to catch.

Lastly, there are efforts underway to develop and review Anti-Money Laundering (“AML”) regulations. The European Commission published draft regulations in July 2021 to establish an EU AML authority and impose a single rulebook to coordinate approaches. While these regulations intend to restrict cybercriminals, it is unclear if these regulations are robust enough to protect consumers against cybercriminal activity in this digital age. Congress and regulators need to keep a close watch to new market entrants in digital payments to ensure regulations are comprehensive and continue to protect consumers against potential fraud in all venues.

Kathleen Denise Arteficio is a third-year JD-MBA student at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

INTRODUCTION

“Zombies” may be pure fiction in Hollywood movies, but they are a very real concern in an area where most individuals would least expect – trademark law. A long-established doctrine in U.S. trademark law deems a mark to be considered abandoned when its use has been discontinued and where the trademark owner has no intent to resume use. Given how straightforward this doctrine seems, it is curious why the doctrine of residual goodwill has been given such great importance in trademark law.

Residual goodwill is defined as customer recognition that persists even after the last sale of a product or service have concluded and the owner has no intent to resume use. Courts have not come to a clear consensus on how much weight to assign to residual goodwill when conducting a trademark abandonment analysis. Not only is the doctrine of residual goodwill not rooted in federal trademark statutes, but it also has the potential to stifle creativity among entrepreneurs as the secondhand marketplace model continues to grow rapidly in the retail industry.

This dynamic has led to a phenomenon where (1) courts have placed too much weight on the doctrine of residual goodwill in assessing trademark abandonment, leading to (2) over-reliance on residual goodwill, which can be especially problematic given the growth of the secondhand retail market, and finally, (3) over-reliance on residual goodwill in the secondhand retail market will disproportionately benefit large corporations over smaller entrepreneurs.

A. The Over-Extension of Residual Goodwill in Trademark Law

A long-held principle in intellectual property law is that “[t]rademarks contribute to an efficient market by helping consumers find products they like from sources they trust.” However, the law has many forfeiture mechanisms that can put an end to a product’s trademark protection when justice calls for it. One of these mechanisms is the abandonment doctrine. Under this doctrine, a trademark owner can lose protection if the owner ceases use of the mark and cannot show a clear intent to resume use. Accordingly, the abandonment doctrine encourages brands to keep marks and products in use so that they cannot merely warehouse marks to siphon off market competition.

The theory behind residual goodwill is that trademark owners may deserve continued protection even after a prima facie finding of abandonment because consumers may associate a discontinued trademark with the producer of a discontinued product. This doctrine is primarily a product of case law rather than deriving from trademark statutes. Most courts will not rely on principles of residual goodwill alone in evaluating whether a mark owner has abandoned its mark. Instead, courts will often consider residual goodwill along with evidence of how long the mark had been discontinued and whether the mark owner intended to reintroduce the mark in the future.

Some courts, like the Fifth Circuit, have gone as far as completely rejecting the doctrine of residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analysis and will focus solely on the intent of the mark owner in reintroducing the mark. These courts reject the notion that a trademark owner’s “intent not to abandon” is the same as an “intent to resume use” when the owner is accused of trademark warehousing. Indeed, in Exxon Corp. v. Humble Exploration Co., the Fifth Circuit held that “[s]topping at an ‘intent not to abandon’ tolerates an owner’s protecting a mark with neither commercial use nor plans to resume commercial use” and that “such a license is not permitted by the Lanham Act.”

The topic of residual goodwill has gained increased importance over the last several years as the secondhand retail market has grown. The presence of online resale and restoration businesses in the fashion sector has made it much easier for consumers to buy products that have been in commerce for several decades and might contain trademarks still possessing strong residual goodwill. Accordingly, it will be even more crucial for courts and policymakers to take a hard look at whether too much importance is currently placed on residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analysis.

B. Residual Goodwill’s Increasing Importance Given the Growth of the Secondhand Resale Fashion Market

Trademark residual goodwill will become even more important for retail entrepreneurs to consider, given the rapid growth in the secondhand retail market. Brands are using these secondhand marketplaces to extend the lifecycles of some of their top products, which will subsequently extend the lifecycle of their intellectual property through increased residual goodwill.

Sales in the secondhand retail market reached $36 billion in 2021 and are projected to nearly double in the next five years to $77 billion. Major brands and retailers are now making more concerted efforts to move into the resale space to avoid having their market share stolen by resellers. As more large retailers and brands extend the lifecycle of their products through resale marketplaces, these companies will also likely extend the lifespan of their intellectual property based on the principles of residual goodwill. In other words, it is now more likely for residual goodwill to accrue with products that are discontinued by major brands and retailers now since those discontinued products are made available through secondhand marketplaces.

The impact of the secondhand retail market on residual goodwill analysis may seem like it is still in its early stages of development. However, the recent Testarossa case, Ferrari SpA v. DU , out of the Court of Justice of the European Union is a preview of what may unfold in the U.S. In Testarossa, a German toy manufacturer challenged the validity of Ferrari’s trademark for its Testarossa car model on the grounds that Ferrari had not used the mark since it stopped producing Testarossas in 1996. While Ferrari had ceased producing new Testarossa models in 1996, it had still sold $20,000 in Testarossa parts between 2011 and 2017. As a result, the CJEU ultimately ruled in Ferrari’s favor and held that production of these parts constituted “use of that mark in accordance with its essential function” of identifying the Testarossa parts and where they came from.

Although Ferrari did use the Testarossa mark in commerce by selling car parts associated with the mark, the court’s dicta in the opinion referred to the topic of residual goodwill and its potentially broader applications. In its reasoning, the CJEU explained that if the trademark holder “actually uses the mark, in accordance with its essential function . . . when reselling second-hand goods, such use is capable of constituting ‘genuine use.’”

The Testarossa case dealt primarily with sales of cars and automobile parts, but the implications of its ruling extend to secondhand retail, in general. If the resale of goods is enough to qualify as “genuine use” under trademark law, then this provides trademark holders with a much lower threshold to prove that they have not abandoned marks. This lower threshold for “genuine use” in secondhand retail marketplaces, taken together with how courts have given potentially too much weight to residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analyses, could lead to adverse consequences for entrepreneurs in the retail sector.

C. The Largest Brands and Retailers Will Disproportionately Benefit from Relaxed Trademark Requirements

The increasingly low thresholds for satisfying trademark “genuine use” and for avoiding trademark abandonment will disproportionately benefit the largest fashion brands and retailers at the expense of smaller entrepreneurs in secondhand retail. Retail behemoths, such as Nike and Gucci, will disproportionately benefit from residual goodwill and increasingly relaxed requirements for trademark protection since these companies control more of their industry value systems. This concept will be explained in more detail in the next section.

Every retail company is a collection of activities that are performed to design, produce, market, deliver, and support the sale of its product. All these activities can be represented using a value chain. Meanwhile, a value system includes both a firm’s value chain and the value chains of all its suppliers, channels, and buyers. Any company’s competitive advantages can be best understood by looking at both its value chain and how it fits into its overall value system.

In fashion, top brands and retailers, such as Nike and Zara, sustain strong competitive advantages in the marketplace in part because of their control over multiple aspects of their value systems. For example, by offering private labels, retailers exert control over the supplier portion of their value systems. Furthermore, by owning stores and offering direct-to-consumer shipping, brands exert control over the channel portion of their value systems. These competitive advantages are only heightened when a company maintains tight protection over their intellectual property.

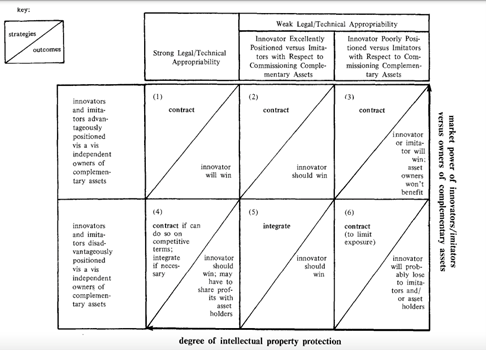

As portrayed in the figure below , companies maintain the strongest competitive advantages in cell one when they are advantageously positioned relative to owners of complementary assets, and they maintain strong intellectual property protection. In such situations, an innovator will win since it can derive value at multiple sections of its value system using its intellectual property.

CONCLUSION

Although there is little case law on the relevance of residual goodwill and secondhand retail marketplaces, it is only a matter of time until the largest fashion brands and retailers capitalize on increasingly low thresholds for demonstrating trademark “genuine use.” Courts and policymakers should now stay alert of these potential issues when dealing with trademark abandonment matters.

Rohun Reddy is a third-year JD-MBA student at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.

The development of AI systems has reached a point at which these systems can create and invent new products and processes just as humans can. There are several features of these AI systems that allow them to create and invent. For example, the AI systems imitate intelligent human behavior, as they can perceive data from outside and decide which actions to take to maximize their probability of success in achieving certain goals. The AI systems can also evolve and change based on new data and thus may produce results that the programmers or operators of the systems did not expect in their initial plans. They have created inventions in different industries, including the drug, design, aerospace, and electric engineering industries. NASA’s AI software has designed a new satellite antenna, and Koza’s AI system has designed new circuits. Those inventions would be entitled to patent protection if developed by humans. However, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has refused to assign the patent rights of these inventions to the AI systems.

The USTPO Denies Patent Rights to AI Systems

In a patent application that listed an AI system, DABUS, as the inventor, the USPTO refused to assign the patent right to DABUS and thus denied the patent application. DABUS invented an emergency warning light and a food container. The USPTO based its decision mainly upon a plain reading of the relevant statutes. 35 U.S.C § 115(a) states that “[a]n application for patent that is filed … shall include, or be amended to include, the name of the inventor for any invention claimed in the invention.” 35 U.S.C § 100(a) defines an “inventor” as “the individual, or if a joint invention, the individuals collectively who invented or discovered the subject matter of the invention.” 35 U.S.C § 115 consistently refers to inventors as natural persons, as it uses pronouns specific to natural persons, “himself” and “herself.” 35 U.S.C § 115 further states that the inventor must be a person who can execute an oath or declaration. The USPTO thus refused to extend its interpretation of “inventor” to an AI system, and it has stated that “interpreting ‘inventor’ broadly to encompass machines would contradict the plain reading of the patent statutes that refer to persons and individuals.

The Federal Circuit follows the same approach. In Beech Aircraft Corp. v. EDO Corp., the Federal Circuit held that “only natural persons can be ‘inventors.’” Therefore, in the current U.S. legal system, patent rights cannot be assigned for AI-generated inventions even though such inventions would be entitled to patent protection had they been created by humans.

Decisions regarding the patent protection for AI-generated inventions have spurred some disputes among academics. The creator of DABUS, Stephen Thaler, insisted that the inventions created by DABUS should be entitled to patent protection because DABUS is a system that can devise and develop new ideas, unlike some traditional AI systems that can only follow fixed plans. Stephen Thaler contends that DABUS has not been trained using data that is relevant to the invention it produced. Therefore, he claims, that DABUS independently recognized the novelty and usefulness of its instant inventions, entitling its invention patent protection. Thaler also raises an argument regarding the moral rights of inventions. Although current U.S. patent law may recognize Thaler as the inventor of these inventions, he emphasizes that recognizing him rather than DABUS as the inventor devalues the traditional human inventorship by crediting a human with work that they did not invent.

Some legal academics support the contentions of Stephen Thaler. For example, Professor Ryan Abbott agrees that AI systems should be recognized as inventors and points out that if in the future, using AI becomes the prime method of invention, the whole IP system will lose its effectiveness.

However, there are also objections to Thaler’s contentions. For example, AI policy analyst Hodan Omaar disagrees that AI systems should be granted inventor status because she believes that the patent system is for protecting an inventor’s economic rights, not their moral rights. She points out that the primary goal of patent law is to promote innovations, but Thaler’s proposed changes to patent law do little to do so. She argues that the value of protecting new inventions is for a patent owner rather than an inventor, which means that it makes no difference who creates the value. Thus, she concludes that listing DABUS as inventor makes no difference to the patent system. Omaar further argues that the proposed changes would introduce a legally unpunishable inventor that threatens human inventors, because the government cannot effectively hold AI systems, unlike individuals or corporations, directly accountable if they illegally infringe on the IP rights of others.

Patent Rights to AI Systems in Other Jurisdictions and Insights on U.S. Patent Law

Some foreign jurisdictions take the same stance as the United States. The UK Court of Appeal recently refused to grant patent protection to the inventions generated by DABUS because the Court held that patent law in the UK requires an inventor to be a natural person.

Despite failing to in the US and UK, Thaler succeeded in getting patent protections for the inventions created by DABUS in some other jurisdictions that allowed listing DABUS as the inventor. South Africa granted patent protection to a food container invention created by DABUS. This is the first patent for an AI-generated invention that names an AI system as the inventor. The decision may be partially explained by the recent policy landscape of South Africa, as its government wants to solve the country’s socio-economic issues by increasing innovation.

Thaler gained another success in Australia. While the decision in South Africa was made by a patent authority, the decision in Australia is the first decision of this type made by a court. The Commissioner of Patents in Australia rejected the patent application by Thaler, but the Federal Court of Australia then answered the key legal questions in favor of permitting AI inventors. Unlike patent law in the US, the Australian Patents Act does not define the term “inventor.” The Commissioner of Patents contended that the term “inventor” in the Act only refers to a natural person. However, Thaler successfully argued to the Court that the ordinary meaning of “inventor” is not limited to humans. The Court noted that there is no specific aspect of patent law in Australia that does not permit non-human inventors.

Examining the different decisions regarding the patent application of DABUS in different jurisdictions, we can see that the different outcomes may result from different policy landscapes and different patent law provisions in different jurisdictions.

For example, South Africa has a policy landscape where it wants to increase innovation to solve its socio-economic issues, while in the U.S., the government may not have the same policy goals related to patent law. Australia’s patent law does not limit an “inventor” to mean a natural person, while U.S. patent law specifically defines the word “inventor” to exclude non-human inventors in this definition. Thus, it is reasonable for U.S. patent law not to grant patent rights to AI-systems for AI-generated inventions, unless the legislature takes actions to broaden the definition of “inventor” to include non-human inventors.

The primary goal of the U.S. patent law is to promote innovation. If those who want to persuade the U.S. legislature to amend the current patent law to allow non-human inventors cannot demonstrate that such a change is in line with that primary goal, then it is unlikely that the legislature would support such a change. Whether granting patents to AI systems and allowing those systems to be inventors can promote innovation is likely to be an ongoing debate among academics.

Jason Chen is a third-year law student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.