DEAD OR ALIVE: ANALYZING THE IMPACT OF TRADEMARK RESIDUAL GOODWILL ON ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN FASHION

INTRODUCTION

“Zombies” may be pure fiction in Hollywood movies, but they are a very real concern in an area where most individuals would least expect – trademark law. A long-established doctrine in U.S. trademark law deems a mark to be considered abandoned when its use has been discontinued and where the trademark owner has no intent to resume use. Given how straightforward this doctrine seems, it is curious why the doctrine of residual goodwill has been given such great importance in trademark law.

Residual goodwill is defined as customer recognition that persists even after the last sale of a product or service have concluded and the owner has no intent to resume use. Courts have not come to a clear consensus on how much weight to assign to residual goodwill when conducting a trademark abandonment analysis. Not only is the doctrine of residual goodwill not rooted in federal trademark statutes, but it also has the potential to stifle creativity among entrepreneurs as the secondhand marketplace model continues to grow rapidly in the retail industry.

This dynamic has led to a phenomenon where (1) courts have placed too much weight on the doctrine of residual goodwill in assessing trademark abandonment, leading to (2) over-reliance on residual goodwill, which can be especially problematic given the growth of the secondhand retail market, and finally, (3) over-reliance on residual goodwill in the secondhand retail market will disproportionately benefit large corporations over smaller entrepreneurs.

A. The Over-Extension of Residual Goodwill in Trademark Law

A long-held principle in intellectual property law is that “[t]rademarks contribute to an efficient market by helping consumers find products they like from sources they trust.” However, the law has many forfeiture mechanisms that can put an end to a product’s trademark protection when justice calls for it. One of these mechanisms is the abandonment doctrine. Under this doctrine, a trademark owner can lose protection if the owner ceases use of the mark and cannot show a clear intent to resume use. Accordingly, the abandonment doctrine encourages brands to keep marks and products in use so that they cannot merely warehouse marks to siphon off market competition.

The theory behind residual goodwill is that trademark owners may deserve continued protection even after a prima facie finding of abandonment because consumers may associate a discontinued trademark with the producer of a discontinued product. This doctrine is primarily a product of case law rather than deriving from trademark statutes. Most courts will not rely on principles of residual goodwill alone in evaluating whether a mark owner has abandoned its mark. Instead, courts will often consider residual goodwill along with evidence of how long the mark had been discontinued and whether the mark owner intended to reintroduce the mark in the future.

Some courts, like the Fifth Circuit, have gone as far as completely rejecting the doctrine of residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analysis and will focus solely on the intent of the mark owner in reintroducing the mark. These courts reject the notion that a trademark owner’s “intent not to abandon” is the same as an “intent to resume use” when the owner is accused of trademark warehousing. Indeed, in Exxon Corp. v. Humble Exploration Co., the Fifth Circuit held that “[s]topping at an ‘intent not to abandon’ tolerates an owner’s protecting a mark with neither commercial use nor plans to resume commercial use” and that “such a license is not permitted by the Lanham Act.”

The topic of residual goodwill has gained increased importance over the last several years as the secondhand retail market has grown. The presence of online resale and restoration businesses in the fashion sector has made it much easier for consumers to buy products that have been in commerce for several decades and might contain trademarks still possessing strong residual goodwill. Accordingly, it will be even more crucial for courts and policymakers to take a hard look at whether too much importance is currently placed on residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analysis.

B. Residual Goodwill’s Increasing Importance Given the Growth of the Secondhand Resale Fashion Market

Trademark residual goodwill will become even more important for retail entrepreneurs to consider, given the rapid growth in the secondhand retail market. Brands are using these secondhand marketplaces to extend the lifecycles of some of their top products, which will subsequently extend the lifecycle of their intellectual property through increased residual goodwill.

Sales in the secondhand retail market reached $36 billion in 2021 and are projected to nearly double in the next five years to $77 billion. Major brands and retailers are now making more concerted efforts to move into the resale space to avoid having their market share stolen by resellers. As more large retailers and brands extend the lifecycle of their products through resale marketplaces, these companies will also likely extend the lifespan of their intellectual property based on the principles of residual goodwill. In other words, it is now more likely for residual goodwill to accrue with products that are discontinued by major brands and retailers now since those discontinued products are made available through secondhand marketplaces.

The impact of the secondhand retail market on residual goodwill analysis may seem like it is still in its early stages of development. However, the recent Testarossa case, Ferrari SpA v. DU , out of the Court of Justice of the European Union is a preview of what may unfold in the U.S. In Testarossa, a German toy manufacturer challenged the validity of Ferrari’s trademark for its Testarossa car model on the grounds that Ferrari had not used the mark since it stopped producing Testarossas in 1996. While Ferrari had ceased producing new Testarossa models in 1996, it had still sold $20,000 in Testarossa parts between 2011 and 2017. As a result, the CJEU ultimately ruled in Ferrari’s favor and held that production of these parts constituted “use of that mark in accordance with its essential function” of identifying the Testarossa parts and where they came from.

Although Ferrari did use the Testarossa mark in commerce by selling car parts associated with the mark, the court’s dicta in the opinion referred to the topic of residual goodwill and its potentially broader applications. In its reasoning, the CJEU explained that if the trademark holder “actually uses the mark, in accordance with its essential function . . . when reselling second-hand goods, such use is capable of constituting ‘genuine use.’”

The Testarossa case dealt primarily with sales of cars and automobile parts, but the implications of its ruling extend to secondhand retail, in general. If the resale of goods is enough to qualify as “genuine use” under trademark law, then this provides trademark holders with a much lower threshold to prove that they have not abandoned marks. This lower threshold for “genuine use” in secondhand retail marketplaces, taken together with how courts have given potentially too much weight to residual goodwill in trademark abandonment analyses, could lead to adverse consequences for entrepreneurs in the retail sector.

C. The Largest Brands and Retailers Will Disproportionately Benefit from Relaxed Trademark Requirements

The increasingly low thresholds for satisfying trademark “genuine use” and for avoiding trademark abandonment will disproportionately benefit the largest fashion brands and retailers at the expense of smaller entrepreneurs in secondhand retail. Retail behemoths, such as Nike and Gucci, will disproportionately benefit from residual goodwill and increasingly relaxed requirements for trademark protection since these companies control more of their industry value systems. This concept will be explained in more detail in the next section.

Every retail company is a collection of activities that are performed to design, produce, market, deliver, and support the sale of its product. All these activities can be represented using a value chain. Meanwhile, a value system includes both a firm’s value chain and the value chains of all its suppliers, channels, and buyers. Any company’s competitive advantages can be best understood by looking at both its value chain and how it fits into its overall value system.

In fashion, top brands and retailers, such as Nike and Zara, sustain strong competitive advantages in the marketplace in part because of their control over multiple aspects of their value systems. For example, by offering private labels, retailers exert control over the supplier portion of their value systems. Furthermore, by owning stores and offering direct-to-consumer shipping, brands exert control over the channel portion of their value systems. These competitive advantages are only heightened when a company maintains tight protection over their intellectual property.

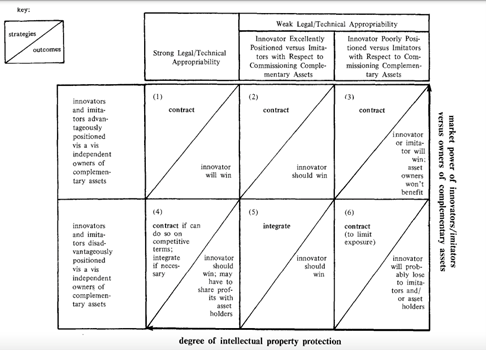

As portrayed in the figure below , companies maintain the strongest competitive advantages in cell one when they are advantageously positioned relative to owners of complementary assets, and they maintain strong intellectual property protection. In such situations, an innovator will win since it can derive value at multiple sections of its value system using its intellectual property.

CONCLUSION

Although there is little case law on the relevance of residual goodwill and secondhand retail marketplaces, it is only a matter of time until the largest fashion brands and retailers capitalize on increasingly low thresholds for demonstrating trademark “genuine use.” Courts and policymakers should now stay alert of these potential issues when dealing with trademark abandonment matters.

Rohun Reddy is a third-year JD-MBA student at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law.